4848

Winthrop Tower

Site #3 Description…

A major chapter in the story of poor people’s movements for affordable housing was the fight for tenants’ rights in buildings subsidized by HUD (Department of Housing and Urban Development). This stop on our tour focuses on 4848 North Winthrop, also known as Winthrop Towers or the 4848. In the late 1960s and early 70s, widespread economic crisis and a related loss of faith in government-owned housing on the part of both Democrats and Republicans led to HUD setting up a public-private partnership model for building subsidized housing. Private developers could now avail mortgages at low, HUD-insured rates, provided that they retain the housing built this way as low-income housing for at least 25 years. Eleven such buildings were constructed in Uptown, wholly or partially comprising Section 8 housing. Winthrop Towers was one of these buildings. Built in 1969, the towers developed a reputation for crime during the late 70s, and by the early 80s HUD had foreclosed on the building and was looking to sell it to a redeveloper. It was at this critical juncture that tenants organized themselves, demanding housing justice and control over their homes. With the help of Travellers and Immigrants Aid, the residents of 4848 N Winthrop were able to transition the building to co-op ownership in the late 1990s.

This footage from the 1970s shows protestors gathering outside of the downtown Chicago Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) office. The speaker is holding a jar with many cockroaches, which she claims to have caught in only a 20 minute span in her Uptown apartment. Later in the video she displays a cake decorated with cockroaches and mice that the protestors are hoping to deliver to John Davis, Director of Property Disposition in the Chicago Area HUD Office. From "Social and Political Intervention Scrapbook," Communications for Change, Media Burn Archive’s Guerrilla Television collection. Reproduced with the permission of Media Burn Archive.

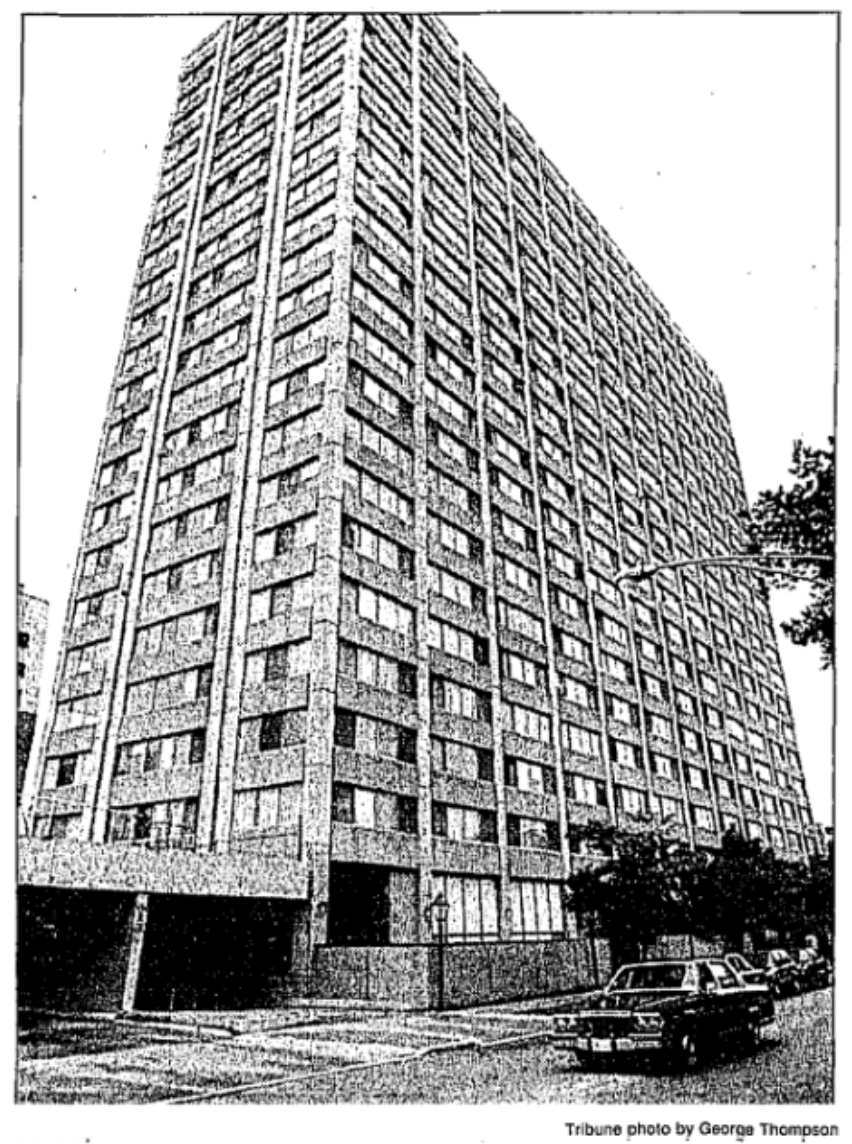

Winthrop Towers. Source: “Saving Our Homes,” Center for Urban Research and Learning, 1996.

The “Section 8” or the Housing Choice Voucher program is one among the many affordable housing programs administered by HUD (others are administered by the Chicago Housing Authority, or directly by the City of Chicago). Its popular name comes from being based on Section 8 of the Housing Act of 1937. The program allows individuals with very low income, including the elderly and disabled, to acquire vouchers that can be used to subsidize rent in any housing that participates in the Section 8 program, whether the building is classified as low-income housing or not. Landlords who agree to set aside units in their building for Section 8 housing are also offered subsidies by the government. The Section 8 Program was authorized by Congress in 1974 and represents part of the previously discussed shift away from government-owned housing, in this case, towards government provided vouchers in privately owned buildings, the construction of which was subsidized by the state.

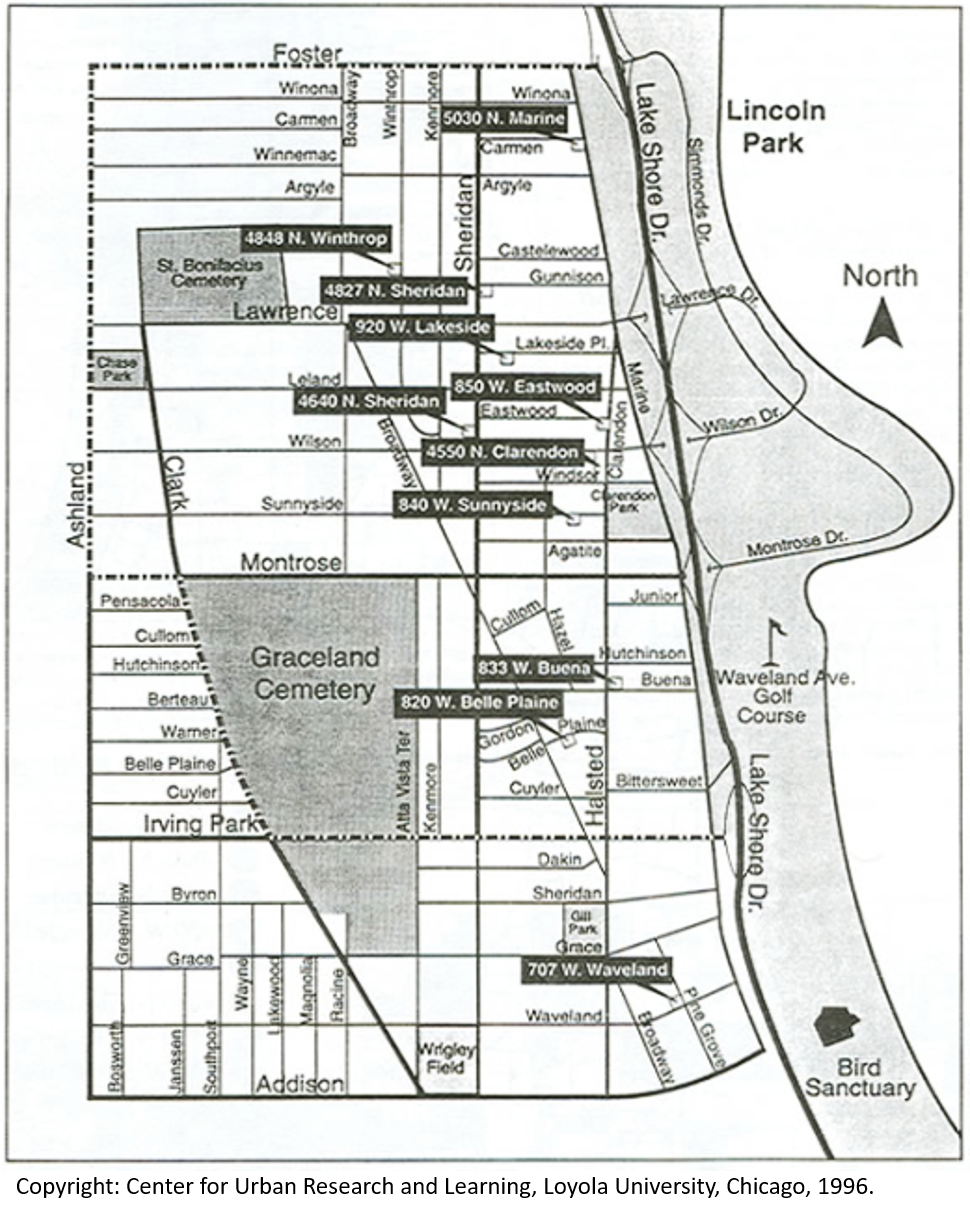

A map showing all of the HUD-insured high rises in the Uptown area. Source: Saving Our Homes, Loyola, 1996

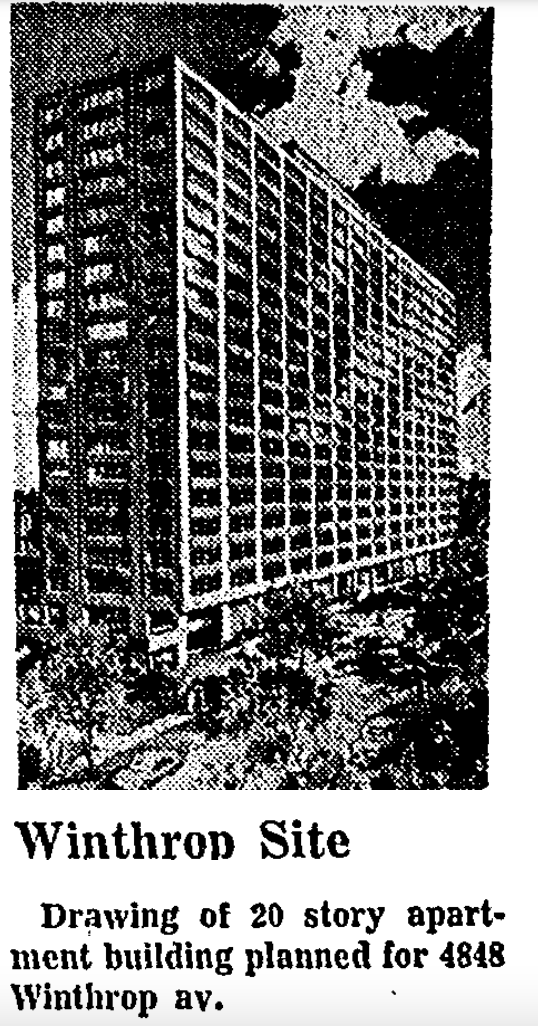

A 1968 drawing of the soon-to-be-built Winthrop Towers. Source: Chicago Tribune

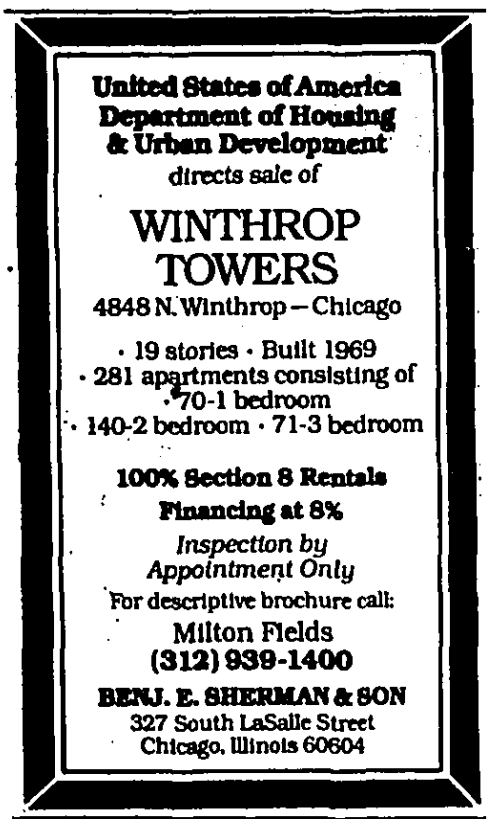

An classified ad from 1970 touts the many amenities of the new Winthrop Towers. Source: Chicago Tribune

1987 press conference held in front of 4848 N Winthrop. Several aldermen, including Helen Shiller (seen here speaking), and state representatives held a press conference in front of the building in which they called on HUD to address maintenance issues at 4848 and other such buildings around the city. Courtesy of Helen Shiller.

The private developers that HUD initially partnered with tended not to address long-standing issues of poor maintenance and unlivable conditions in these buildings. In fact, they regularly used these conditions to encourage the exodus of poor tenants, hoping to accelerate the conversion of HUD subsidized affordable housing into market-rate properties. Winthrop Towers was similarly neglected and became infamous as “the 4848”—a hub of crime, drugs, and prostitution—with police raids uncovering weapons caches and national-level gang networks. The building was foreclosed on in 1981 and acquired by HUD, which continued the mismanagement.

Slumlord politics is an age-old issue in Uptown, as we saw in the aftermath of Truman College’s construction. With no incentive to retain low-income tenants, and in the absence of regulation and enforcement, buildings with poor tenants faced unspeakable negligence. Once, a two-year-old baby was killed by the descending elevator car in her building when she looked down the unprotected elevator shaft. As this video shows, other buildings were evicted of their tenants and simply left abandoned without guards, creating dangerous conditions.

HUD refused to sell the building when a developer bid for it in 1983, citing bureaucratic fine points. Some reports at the time attributed this to “bureaucratic stupidity” and, more revealingly, to a million-dollar scam. In the late 1980s, HUD became subject to a congressional investigation for favoritism in granting contracts to private companies. In the case of Winthrop Towers, the developer’s 1983 bid was rumored to have been rejected in favor of a bid made by the private maintenance company hired by HUD to oversee the apartment. The private company’s $1 million per year maintenance fee was dubious considering the condition of the building. All the while, the conditions in Winthrop Towers continued to deteriorate under HUD’s ownership. Life was hell for the tenants who had nowhere else to go, but a turn of events soon created a climate for change.

A 1987 Keep Strong magazine header highlights the scale of the prepayment struggle in HUD buildings throughout the city. There were 11 of these HUD-insured buildings in Uptown. Source: Keep Strong September/October 1987. Courtesy of Helen Shiller.

A 1983 ad shows HUD testing the market. Source: Chicago Tribune

In the 1980s, landlords discovered a loophole in the HUD mortgage conditions that allowed them to pay off the mortgage (prepayment) and convert the buildings into market-value housing, and they began the procedure to do so. According to a report authored by a research group at Loyola University based on its work with Organization of the North East (ONE), it was this move towards prepayment by private owners that spurred the tenants in many of these buildings to act together to save their homes. Without successful collective action many of these low income tenants would be left homeless.

Winthrop Towers—having been foreclosed on and placed into receivership—did not face the threat of prepayment like other HUD subsidized buildings still owned by private developers. However, the impending sale of the building catalyzed the residents to organize—to try to ensure that they would have a say in how the building was run in the future. Like inside the prepayment buildings, the tenants of Winthrop Towers worked with ONE to look for a suitable buyer who would help them transition to a co-operative model.

In 2013, ONE joined with the Lakeview Action Coalition to form ONE Northside, currently one of the most prominent Uptown organizations leading struggles for education, housing, and justice for poor and homeless people. The threat of prepayment catalyzed the creation of tenant organizations in the HUD subsidized buildings, and these associations leaned on community groups like ONE and Voice of the People for guidance and legal resources. ONE had helped make tenants aware of the threat of prepayment by showing them the results of their 1988 survey that showed most owners planned to prepay their HUD mortgages, and ONE’s greater financial resources were useful for tenant associations that relied solely on membership dues.

Dan Burke, a lawyer who represented tenants of a neighboring HUD building describes the prepayment threat to the Chicago reader in 1988:

“‘The legal term is prepayment of mortgage…[b]asically, it means that the owner pays off his mortgage, and is no longer bound by HUD regulations. Without government action, the landlords could raise rents and displace people. In Chicago there are 91 [similar] buildings containing 17,240 units, which means at least 60,000 tenants whose mortgages hit the 20-year mark between 1988 and 1992. That could mean a lot of people in the street.’” (emphasis added)

In Winthrop Towers, the tenant organization and ONE created the conditions for Century Place Development Corporation (CPDC), a non-profit developer and branch of the social service agency Travellers and Immigrants Aid, to acquire the building in 1993 in order to improve it without displacing the existing tenants. As with other non-profit takeovers, the ultimate aim was to have tenants take over ownership and management of the building—Winthrop Towers tenants would be given the option of buying the building after 5 years of CPDC management.

Initially, the tenants at the 4848 were justifiably wary of CPDC, and each other, after a decade of social breakdown and exploitation by building owners, including HUD. For tenants to work together was not always easy—residents were among the poorest people in the city and tensions could run high in Winthrop Towers. The building housed an extremely diverse group of Black, Native American, and Hispanic families, as well as immigrant families from Southeast Asia, the erstwhile Soviet Union, and Africa. In some cases, inter-communal tensions led to the failure of collective tenant movements—in Winthrop Towers, the diversity of communities was a challenge to be overcome.

A 1993 headline chronicles the sale of Winthrop Towers to the non-profit developer Century Place Development Corporation (Travelers & Immigrants Aid). Source: Chicago Tribune

HUD solicits proposals for non-profit ownership in a 1992 advert with an asking price of $1 and the stipulations that the owner must invest $5 million in repairs and assure that ownership is handed over to tenants as a co-operatively owned building within 5 years. Source: Chicago Tribune

The entryway to United Winthrop Tower Cooperative. Source: unitedwinthroptowercooperative.com

CPDC’s investment in improving the building with tenant participation in decision-making, and its careful politics of building trust, eventually won over the reticent group. CPDC’s Larry Pusateri was critical in making the sale and conversion work. Tenants spoke of Pusateri’s commitment to addressing resident’s needs and his transparent dealings with the building’s tenant Union.

Once acquired by CPDC/Travellers and Immigrants Aid, 4848 N Winthrop was incorporated into the agency’s Families Building Communities program, an effort by the group to address homelessness by giving unhoused persons a place to stay and access to intensive services to help get them back on their feet. Travellers and Immigrants Aid invested $5 million into the building and oversaw its transition to tenant ownership. Today, Winthrop Towers is a fully tenant-owned cooperative housing unit. However, co-op organization is not without its challenges.

Listen to 29 year-old Kwame Freeman speak about growing up in “the 4848” in the 1990s. Kwame’s experiences shaped his role as a youth organizer with the Multicultural Youth Project (MCYP) in Uptown.

A rich lineage of tenant-organized movements helps to inform the history of affordable housing in Uptown: JOIN’s tenant unions and successful rent strikes in the late 1960s, the tenant survival committees set up by the ISC during the 1970s, the anti-prepayment struggles in HUD buildings of the 1980s, and the Tent City resistance to homelessness in the 2000s. All of these examples remind us that tenants themselves, rather than representative organizations alone, have been a crucial part of the battle for retaining low and mixed income housing in the Uptown area. That Uptown remains among the most racially diverse neighborhoods in Chicago is testament to the painstaking efforts of several such tenants’ movements.

Wilma Pittman. Photo by Kenneth Allen.

Wilma Pittman—board member at Northside Action for Justice (NA4J), longtime resident of 4848 N Winthrop, and former United Winthrop Tower Cooperative board member—spoke with us about her experiences in Winthrop Tower since moving there in 2005.

“I had no idea what a co-op was. You pay your first month’s rent—well housing charges, they call it housing charges— and you get your certificate that says you have one share in the co-op. If you move out, you have to sell your one share back to them [the co-op board] and they give it to someone else. You’re thinking ‘Ooo I have one share… this is mine,’ but it really is not. The only difference [from renting] is you have to pay—if I accidentally pull off my refrigerator handle, I have to pay for that.”

On living in a large and diverse building:

“It’s the respect, if you can respect people—even if you’re not speaking the same language you can have a beautiful relationship, so that’s what I have learned.”

Wilma Pittman speaks about the neighborliness she has encountered in the co-op, and the issues that unite members of all backgrounds.

However, the current management and co-op board of 4848 N Winthrop, or United Winthrop Tower Cooperative, have issues with transparency. They have restricted certain political representatives from entering the building, including the present alderwoman, and have worked to keep out local tenant organizers as well. One issue that is particularly disturbing is the eviction of vulnerable families from Winthrop Tower, a process which is often driven by personal animosity between management and individual tenants.

Wilma reflects painfully on the eviction of vulnerable families from the co-op—specifically the memory of a disabled couple with numerous children being put out.

In each of the HUD prepayment struggles, the methods, outcomes, and challenges were different. What these conflicts established, however, was a powerful common moment where tenants incessantly took to task corporate and government housing agencies, using the community resources available to them, and setting an example for tenant movements in the rest of the US. A notable aspect of these movements was that most of them were led by women, many of them single mothers. What this demonstrates is not just that single women-headed households are subject to added vulnerability, but also that their resilience and resourcefulness, born of need, was truly revolutionary.

Winthrop Tower in May of 2024. Photo: Kenneth Allen

A 1989 Photo of 920 West Lakeside. Photo: George Thompson; Source: Chicago Tribune.

920 W. Lakeside was one of the first HUD-subsidized buildings to assemble a powerful tenant association, the Lakeside Tenants Organization (LTO). During the mid-1980s, the LTO fought back against ownership’s neglect of the building, and was able to get the owner’s management company fired after years of failing to maintain the property. The next challenge for the LTO was the sale of the building—working with Voice of the People, the LTO established the Chicago Community Development Corporation (CCDC), a non-profit organization through which they hoped to purchase the building from private ownership. Unfortunately, the CDCC was outbid by a Texas- and Louisiana-based real estate group headed by the Barineau family. Once the building was sold, rents jumped between $150-300 for those units which were not Section 8, but which had been paying below “market-rate” rent. Approximately 60 families had to move as a result of this rent hike, and those forced out were largely African American. These vacated units were filled mostly by Russian immigrant families, which contributed to worsening ethnic and racial tensions in the building, and damaged the LTO’s organizing base. Although they were ultimately unsuccessful in securing non-profit or cooperative ownership, the LTO provided a model of organizing to other HUD building residents.

The Carmen-Marine became the first tenant-owned low-income housing project in the country in 1991. Lakeview Towers was acquired by Voice of the People, a community organization, becoming the first former HUD-building owned by a community-based non-profit in Illinois. Racial tensions seriously impeded the tenant organization’s working in Sunnyside Apartments, resulting in only short term gains. In both Sunnyside Apartments and 920 W. Lakeside, the movement for retaining low-income housing is ongoing even today.

Copyright ©2018 Dis/Placements ProjectSources:

Please reach out to displacements.chicago@gmail.com for further information regarding source materials.