Art as Activism

Amplify the soul: art as activism

site #10 description…

Youth activism takes centerstage, using music and visual arts as a medium/mode of expression and protest.

Kevin Dao, ex-MCYP member, remembers how the Multicultural Youth Project provided a space to amplify their voices.

What counts as art? Do classical music concerts and paintings and sculptures in museums come to mind? Indeed, Uptown in the Roaring Twenties had been a center of film, music, and theater production catering to the elite. People of color often performed in these spaces with little hope for creative control or adequate payment. Performance forms like vaudeville and minstrelsy, even as they rarely employed African American performers, relied on racist tropes to make a white audience laugh.

However, art and artistic enterprise of a different kind has been integral to sustaining the energies of “Poor People’s Power” in Uptown. Uptown’s more radical legacy of using art to center the experiences and resistance of poor people of color continues to be upheld by a younger generation of artist-activists. They use street-based art forms like hip-hop and murals to speak about oppression, discrimination, and trauma in order to unite people in resistance. Such art forms often promote knowledge-sharing that centers and involves the people of the community as producers of knowledge and agents of social change.

Community Theater in Uptown

ommunity theater in Uptown has a long history. In the early days of Chicago's theater scene, around the 19th century, performances were restricted to the Loop area, featuring expensive and elaborate setups. The "Little Theater Movement" in the early 20th century diversified theater in Chicago, taking it outside this exclusive sphere, and leading to more experimental and politically informed styles, as well as theater productions staged for, and by, neighborhood communities. Chicago's Hull House Theater emerged during this era as the country's first community theater. Under the aegis of well-known social worker Jane Addams, the Theater featured productions that involved working class talent, and spoke to workers' lives. However, these continued to center European migrant experiences, and people of color continued to be marginalized. The Hull House's Uptown center also had a theater space.

A playbill of a 1924 production staged in the Theater, titled "The Mob." Source: https://explore.chicagocollections.org/image/newberry/115/542kd84/ Courtesy: Newberry Library

Ironically, it was during the Great Depression that African American artists and talents were supported. Under Franklin Roosevelt's wide-ranging New Deal program aimed to rejuvenate the American Economy, Federal Theater Projects in cities like Chicago set up "Negro Units" to specifically support Black theater artists in their livelihood. These became hubs of overtly political, anticapitalist and antiracist theater, as a result of which Negro Units were quickly shut down by Senator McCarthy's House Un-American Activities Committee in 1939.

A playbill for a short-lived "African" adaptation of Shakespeare's Lysistrata by the Negro Unit in Washington, Seattle. Spike Lee's 2015 film, Chiraq, is also loosely based on this play. Courtesy: University of Washington Library, Special Collections Division.

In 1965, well-known director Robert Sickinger took over the Hull House Uptown Theater. Under his leadership, the Theater saw racially inclusive and politically charged plays that made a mark on the Chicago scene. In 1976, he invited Jackie Taylor, a young Black theater artist, to set up her Black Ensemble Theater in the space. Jackie Taylor grew up in the Cabrini-Green housing project, and resented the racism she faced as an aspiring theater artist. With the stated aim of eradicating racism, BE has a long history of working with the community, using theater to help inner city school students feel confident and heard, understand classroom concepts better; hosting an annual job training program that trains young Black students with job-seeking skills like resume-building and in theater-related work like acting, writing, set design, and lighting.

Jackie Taylor speaks about the BE's place in Uptown and how she is always questioned about her decision to locate the Theater not in the south side, but the north side of Chicago.

Source: ABC 7 Chicago interview, 2018 (via YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F-YkZKZ55Ps).

The BE’s regular productions, like The Other Cinderella, written by Jackie Taylor, feature largely African American talent and production teams, and center Black lives and culture. The BE specializes in musical stagings of the lives of famous Black personas like Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye, and Josephine Baker. Historically, they have also staged the works of radical Black playwrights like Lorraine Hansberry and Ed Bullins. In 2011, the Black Ensemble Theater moved from its Hull House home to a newly built, 20-million-dollar facility, the Black Ensemble Theater and Cultural Center, notably built in Uptown. The BE in Uptown, clearly, balances a place in both community theater and mainstream theater.

Youth Activism and the Arts

The title of this post refers to the lyrics in one of John “Vietnam” Nguyen’s songs. In 2012, Nguyen, a young and upcoming hip-hop artist and an active member of the MCYP, drowned saving his friend. “JVN,” as he was popularly known, was a major presence in the artistic scene of Uptown. Uptown’s young artists, many who knew JVN as a friend and mentor, came together to honor JVN’s memory.

Steve Moon draws attention to the ecosystem of youth community organizations that nurtured the talent and leadership of JVN. Courtesy: Asian Americans Advancing Justice website (quote); Asian American Advancing Justice Facebook page (image)

The ecosystem that Moon refers to is one which those like him, Tina Ramirez, Jacinda Bullie, and many others cultivated as mentors to their younger peers in Uptown’s racialized, low-income communities. Creative expression provides spaces for young, racialized people from poor backgrounds to produce transformative knowledge about themselves and their communities. Such a space becomes crucial, when, as we saw, mainstream education is founded on elitist and racist values.

The Multicultural Youth Project was an after-school youth program started by the Chinese Mutual Aid Association in ______. Under able coordinators like Steve Moon and Tina Ramirez, the MCYP fostered a multiracial community of young Uptowners who came to the space to create art, and engage with the issues of the community around them. Apart from providing an informal and safe gathering space, the MCYP conducted workshops around writing, poetry, and art, and even had a recording studio where many like JVN cultivated their hip-hop aspirations. When MCYP came to a close, many alumni, along with new young members, founded Elephant Rebellion, which carries forward MCYP and JVN’s artistic legacy.

The name Elephant Rebellion signals both an ethos as well as an affiliation with MCYP. Source: elephantrebellion.org

Kuumba Lynx was founded in 1996 by three women: Jaquanda Villegas, Leida Garcia, and Jacinda Bullie. Jacinda Bullie was a youth activist in Uptown whose stepfather was a Black Panther. In its performances and workshops, KL uses art forms like hip-hop, breakdancing, and graffiti to engage young people between 8 and 25. KL was formed partly in response to the cutting down of funding for creative and artistic initiatives in the Chicago Public School system. It is most notable for creating a space for young women of color, who are multiply marginalized, to confidently cultivate artistic expression that centers their experiences. The Kuumba Lynx Performance Ensemble is at the forefront of the hip-hop scene in Chicago, and regularly participates in other movements in Uptown, particularly those opposing the cutback of public education. They currently operate from UPLIFT Community High School. Connect Force, similarly, is a hip-hop community group also based in Uptown.

Kuumba Lynx's 2015 promotional video features Jacinda Bullie speaking aboutits aims. Copyright: Kuumba Lynx

As police brutality in low-income racialized communities, restorative justice, the abolition of police and the prioritization of public education all take centerstage today, these groups bring in the strident voices of young people of color into movements.

Murals in Uptown

Murals have, for long, represented an important means to invest public spaces with political meaning, and to articulate community-based resistance, especially among those that are powerless to access political power. The 1960s and 1970s are known as the golden age of muralism in the US. Led by Chicano artists who brought the revolutionary sentiment of Mexican muralism to the US, this era also saw many such radical murals define Chicago's poorer neighborhoods, such as Uptown.

The mural represents a line of faces of different races, all facing the (then) newly built college. In a single outstretched hand is the note with the word, "IOU," a powerful reminder by artist-activists of the sacrifices that were made for the community college. The college displaced thousands of poor white migrants and thwarted their community-centric plan for a "Hank Williams Village" in the space.

Photo credit: Devin Hunter, 2013. Source: Devin Hunter, "Neglected, Seemingly Forgotten Chicago Mural Is Now Extinct, Seemingly Forgotten," Lakefront Historian (blog), November 19, 2014.

One such mural was painted on the wall of the Wilson CTA station viaduct (above), representing the injustices behind the decision to build Truman College by displacing Appalachian migrants. Around the 2010s, the wall was razed, erasing a public reminder of the activism of Uptown's Appalachian migrants.

After some controversy, the faces of Che Guevara and Angela Davis were blacked out on the mural, and painted over with the words "Truth" (left) and "Community" (right) respectively. Image courtesy: Candice Rai

In 2005, another mural was partially erased, this time in the midst of great contention in the community. As part of a workshop led by Kuumba Lynx, the students of Uplift Community High School painted a mural on a wall adjacent to the school, with the permission of the organization that owned the building. Featuring the terms "Uplift," "Community," and "Social Justice" in graffiti style, the mural was also flanked by images of revolutionaries Che Guevarra of the Cuban revolution and Angela Davis of the Black Panther Party. The latter incited protests, largely online, among a section of Uptown's residents who thought the figures were militant and unpatriotic models for poor students of color, and would incite them into joining gangs. After much debate, and despite Uplift's and KL's efforts to defend the choices students made and to discuss matters through an open forum, the faces were blackened out.

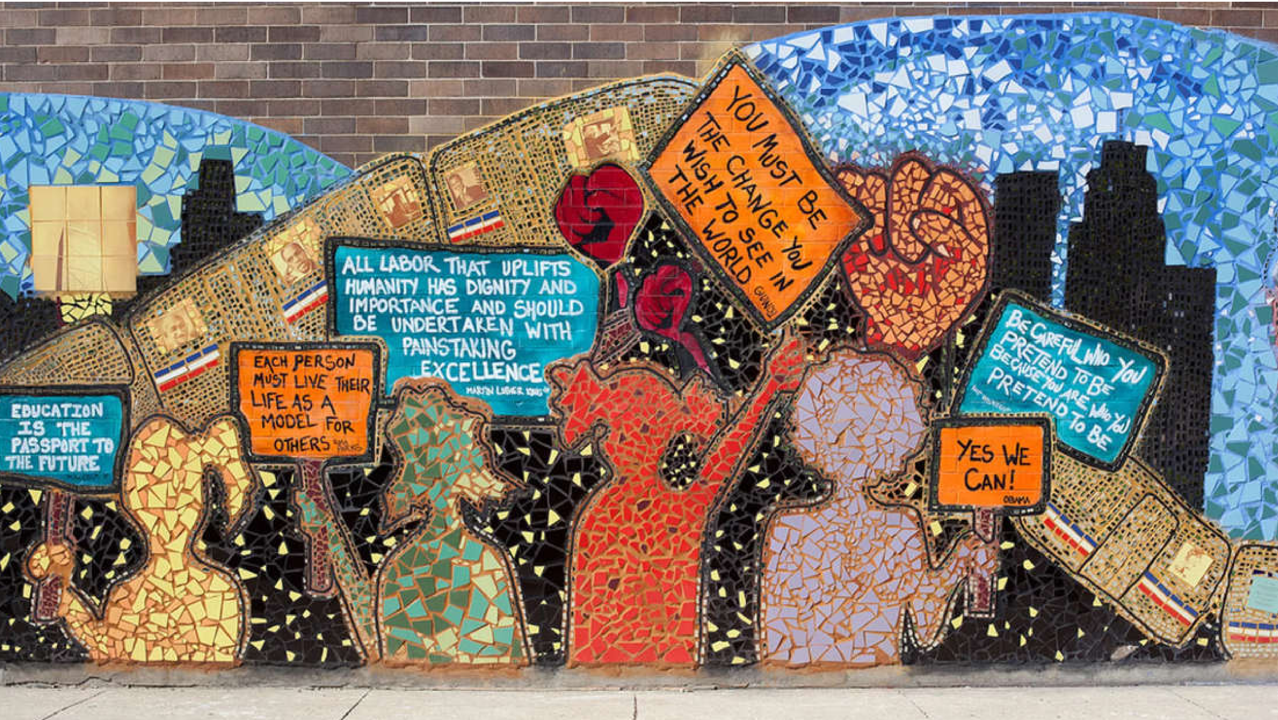

A more recent mosaic-based mural on the Uplift school building, created by the artist collective Green Star Movement with the participation of students, bears more "neutral" messages of social justice and individual change, and remains uncontroversial. A similar mosaic was created by the same collective at the People's Music School, also with the involvement of students at all stages.

Photo credit: Anna Guevarra

Murals, clearly, are sites where differing opinions within the community are reconciled, or sometimes, erased. The Roots of Argyle mural was painted by muralist Mark Elder through consultations with the community. Funded by Uptown's businesses and part of a "beautification" initiative by the Argyle-Kenmore Block Club, the aim of this mural was to represent Uptown's diversity in a "positive" light, focusing on generational care and support rather than politics. As a result, none of the radical movements of Uptown find representation on the extensive mural, though it provides rich documentation of the various communities and leaders that have shaped Argyle street through the decades. In the form of "time portals" representing various decades, the mural shows the centrality of Asian American communities not just to Argyle, but to the US.

In the form of "time portals" representing various decades, the mural represents the various communities that have called Uptown home. Original image sourced from exploreuptown.org, the website of the Uptown Chamber of Commerce.

The most recent additions to Uptown's iconic murals were born of collective grief and healing. The mural was painted shortly after the death of John "Vietnam" Nguyen, in 2012. Based on the collective labor of Uptown's youth, in whose lives "JVN" was a major presence, the mural celebrates JVN's life and all that he stood for as a young artist-activist.

Each letter in the mural symbolizes John Vietnam and the community that he grew up in:

V - The flag of South Vietnam

I - The Uptown Theater, an icon of Uptown.

E- Year of the Dragon 2012 which is the symbol of the Nguyen dynasty

T- An image of a traditional Vietnamese woman that is in a boat along the Mekong River

N- Children getting educated

A- The Argyle station

M- The elephant, which is the symbol for the Multi-Cultural Youth Project that John Vietnam grew up with.

Certain art forms with a long history of being used by the oppressed as forms of political expression and as tools for social change, such as theater, murals, hip-hop, and graffiti, have a significant presence in Uptown. As JVN sang, what they do is "amplify the soul" of Uptown's poor and migrant communities, entailing contention and cooperation, and expressing grief, anger, resilience, and joy. By tracing their histories, we also learn about the lives that are represented, and sometimes, unjustly erased in the stories that Uptown tells about itself.

We would like to thank Colin Goss for compiling material on the history of Black theater and community theater in Chicago. Details about the blackened Uplift mural were sourced from Professor Candice Rai's writings.

Copyright ©2018 Dis/Placements Project