Heiwa Terrace

Heiwa Terrace

Site #5 Description…

Heiwa Terrace is a 12-story apartment building that provides federally subsidized housing and services for seniors and those who require wheelchair accessible housing. “Heiwa” is a Japanese word that translates to “peace” in English. Heiwa Terrace was opened in 1980 and is owned and operated by the Japanese American Service Committee Housing Corporation, a not-for-profit organization. The story of Heiwa Terrace is intertwined with the story of Japanese American resettlement during and after World War II. Relocation of Japanese Americans to Chicago in the 1940s made the city arguably the most important center of Japanese American life in the United States during that decade.

Historical images of Heiwa Terrace’s entryway, garden, and lobby. Source: heiwaterrace.org.

Prisoners unload coal at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center. The Heart Mountain camp is well known for the draft resistance group the Fair Play Committee that was formed at the camp in 1944, following the extension of the draft to imprisoned Nisei that year. Source: Records of the War Relocation Authority, National Archives (use unrestricted, identifier: 538770).

In February of 1942, a few months after the US had declared war on Japan in response to the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delanoe Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the forced evacuation and relocation of all persons who might be considered a “security threat” from “military areas.” In practice this authority was used to racially target Japanese Americans for removal from the West Coast states. While this violation of Japanese American civil rights is often viewed in the limited context of World War II, it is better understood as the latest in a long string of efforts by nativist Whites to challenge Japanese and other Asian Americans’ rights to the benefits of US citizenship. Nisei (first generation US-born Japanese Americans) should have been protected against racist exclusion by the equal protections clause of the 14th Amendment. However, the longstanding efforts of western Whites to strip Japanese Americans of their birthright citizenship were given a federal green light with the advent of war.

Executive Order 9066 was met with resistance from some, including well known figures like Fred Korematsu and journalist James Omura, who were either imprisoned or forced to flee to less vulnerable areas of the country. However, the largest Japanese American civil rights organization of the time, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), assented to the executive order and even collaborated with the War Relocation Authority to identify potentially “disloyal” Issei (foreign-born Japanese immigrants to the US). Individuals and families of Japanese descent were separated from the vast majority of their worldly possessions and imprisoned in camps far from their homes. The process of internment was dehumanizing and conditions in the camps were substandard as a rule and in many cases truly abysmal. Educational facilities were totally inadequate in spite of the large proportion of children among the imprisoned and medical facilities were haphazard.

A Chicago Resettlers Committee English class being conducted in 1946. Source: the Japanese American Service Committee Records, RG 10.

As internees began to be released towards the end of the war, the WRA prevented Japanese Americans from settling in the western states. In addition, some Japanese Americans sought to establish a new life away from the West Coast where they had long faced exclusionary violence and racial discrimination. The Japanese American community of Chicago before World War II numbered around 400 and was based largely on the South Side, in the Hyde Park, Woodlawn and Kenwood areas. Chicago became the number one destination of resettling Japanese Americans during the mid-1940s with some estimating the local population at more than 30,000 in 1945. As an industrial hub facing a labor shortage, there were lots of jobs available to new migrants in wartime Chicago. Japanese Americans seeking to leave the camps before the end of the war had to prove that they had a job lined up so the labor-hungry job market in Chicago was a natural choice.

While Japanese American migrants to Chicago continued to face significant discrimination in housing, work, and social spheres, many noted that the opportunities were better and racism less extreme than what they had experienced in the western US. Additionally, the expanding networks of community and familial bonds supported newcomers and fostered further growth. While approximately half of the community relocated after the war when Japanese Americans were allowed to resettle in the West, by the 1950s the small pre-WWII Japanese population had transformed into a hub of nearly 20,000.

Snapshots of the postwar Japanese American community. Clockwise from top: the Chicago Shimpo masthead from the 1940s (UIC newspapers collection), the Buddhist Temple of Chicago on Leland Ave in the 1960s (Courtesy of the Buddhist Temple of Chicago), and a logo of the Japanese American Service Committee from the 1970s (Courtesy of JASC).

Social service organizations, church groups, and kinship connections were critical to successful relocation in Chicago during the wartime and post-war period. One of the most important service organizations was the Chicago Resettlers Committee (CRC). The group was officially organized in 1944 to provide resources and guidance to recent migrants. One of the greatest challenges for resettlers was finding safe and affordable housing. Excluded from public housing, forced to live in WRA appointed areas, and facing racial discrimination, the shortage of housing soon became a serious issue for the burgeoning community. CRC helped the newcomers utilize public and private resources to obtain housing security. The group soon began serving the Japanese American community at large, not just new migrants, by assisting residents in securing adequate resources in education, and welfare in addition to housing. To represent their wider mission moving forward, in 1954 the organization’s name was changed to the Japanese American Service Committee (JASC). JASC, long based in Uptown, remains a pillar among Chicago’s social service organizations and their founding and management of Heiwa Terrace stands as a critical contribution to affordable housing in the city.

Image collage from JASC’s 1974-75 Annual Report shows Japanese American elders at work in the Senior Citizen Work Center. Courtesy of JASC.

By the time that plans for Heiwa Terrace began to materialize in the mid-1970s, JASC was already established as a provider of services and care for the Japanese American elderly. Programs like the Adult Day Care and Senior Citizen Work Center helped Japanese and other Asian American elders retain a sense of purpose, ward off depression, and stay socially engaged. During the mid-1970s. federal funds were allocated for the construction of low-cost senior housing and JASC polled for the community’s interest.

Heiwa Terrace was built during a period in which affordable housing around the city was in jeopardy—construction of public housing had stagnated because of resistance from the predominantly white City Council to the de-segregating requirements issued as a result of the Gautreaux ruling. However, when Congress passed the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, federal funds became available for the construction of affordable congregate senior housing. Following a survey of the community in 1976, JASC submitted an application to HUD for full funding of a building to provide congregate housing for seniors. A fund-raising campaign in the Japanese American community during 1977 resulted in contributions totaling $180,000, well over their goal of $100,000 and enough cash to kickstart the project. The same year the federal government approved the JASC’s application for a $6.4 million loan for the construction of a 200-unit, 12-story building in accordance with Section 202 of Housing and Community Development Act of 1974.

Clippings from JASC monthly newsletters and annual reports showing the early planning, renderings, and the construction process. Courtesy of JASC.

Ground broke on Heiwa Terrace in 1978 and the building was opened in 1980. Heiwa Terrace has long been revered as a model senior housing and care facility, operating many engagement programs and building bonds between residents with activities like regular communal dinners. Dr. Alice Murata, a historian of Chicago’s Japanese American community and Professor Emeritus of Northeastern Illinois University, served as the president of Heiwa Terrace for over forty years. In that time, Murata collected oral histories from some of the building’s tenants, a decision that sparked her co-founding of the Chicago Japanese American Historical Society (CJAHS). Most of the interviews focused on internment, resettlement, and the redress movement, an effort—mainly led by Nisei—to pressure the US government to apologize and issue financial reparations for Japanese imprisonment during the war.

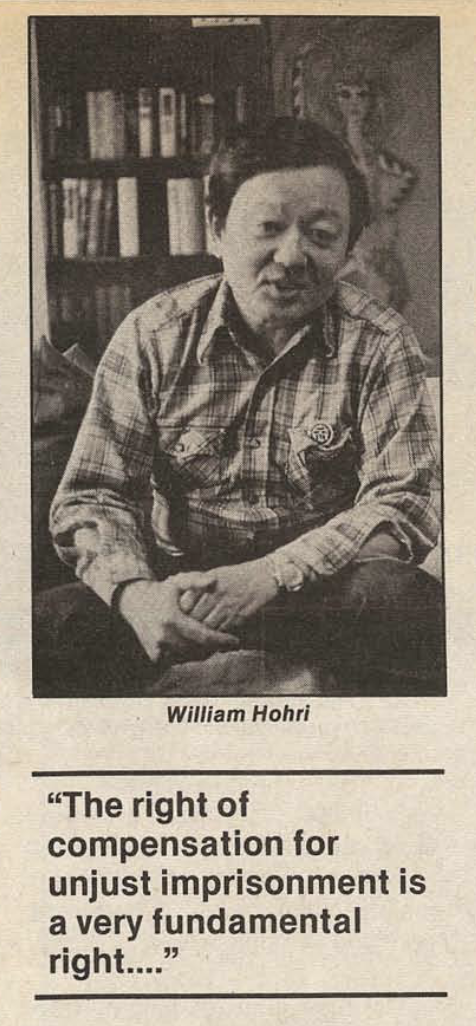

In 1980 the Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians was created by Congress to review the decisions made and actions taken surrounding internment, and recommend “appropriate remedies.” The formation of this commission was the result of decades of civil rights activism by Japanese American individuals and collective organizations pressing the issue of redress. Activist Edison Uno’s work in the 1960s and 1970s was critical to keeping the issue of redress alive in the Japanese American community, and sustaining collective remembrance of the injustices of internment in the national consciousness. Other important individuals in the struggle for redress were researcher Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga and Chicago activist William Hohri. Herzig-Yoshinaga uncovered and organized critical documentary evidence of wrongs committed in the camps, while Hohri led the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR), a group that pushed hard for monetary reparations as part of redress.

Keep Strong magazine, February 1980 issue. Courtesy of Helen Shiller.

In the fall of 1981 hearings for the victims of internment were held in 10 US cities including Chicago. The records of the Chicago hearings are contained in the archives of Northeastern Illinois University (NEIU). Ultimately, the findings of the commission were published in the 1983 report “Personal Justice Denied” which affirmed that “ a grave injustice was done to both citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry” and whose rights were violated “without individual review or any probative evidence against them” in a series of actions “motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The subsequent Civil Liberties Act 1988 granted former internees or their immediate surviving relatives financial reparations in the form of $20,000 checks and a signed presidential apology.

Keep Strong magazine, February 1980 issue. Courtesy of Helen Shiller.

Heiwa Terrace held a small ceremony following the awarding of checks to six residents of the building. Hohri, who spent two years of his teenage life in the camps, and spent decades fighting for monetary reparations, summed it up in a 1990 interview with the Chicago Tribune: "The checks are simply a token, and they are to be accompanied by an apology…They are admissions by the government that what was done to us during the war was in violation of the law and the Constitution.”

A rendering of the updated Heiwa Terrace before its 2020 renovations. Source: heiwaterrace.org

Heiwa Terrace continues to serve the Japanese American, senior, and disabled communities by offering safe and supportive affordable housing. Rent is based on 30% of monthly adjusted income which must be below the building’s market rent of $1,400.00. The minimum age for senior applicants is 62 years old while the minimum age for disabled applicants requiring a wheelchair accessible unit is 18 years old. Heiwa Terrace celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2020 and is currently in the process of being renovated. The $68.4 million renovation has been partially funded by the AFL CIO Housing Investment Trust, and the changes will bring the building up to date and improve its sustainability.

Copyright 2018 Dis/Placements Project

Sources:

Please reach out to displacements.chicago@gmail.com for further information regarding source materials.