Lawrence House

Lawrence House

Site #1 Description…

Lawrence House, much like the Montrose Beach Hotel, has borne witness to the class politics of Uptown and helps us understand how housing policy is a central issue in the debate on urban renewal. The New Lawrence Hotel was built in 1929 to cater to the living needs of the new urban elite, many of whom were young singles or couples. Common facilities provided opportunity for genteel socialization. Celebrities like Frank Sinatra and Henry Kissinger are known to have spent time in the building. A few years after being sold in 1962, The New Lawrence Hotel became Lawrence House, a retirement hotel for well-to-do senior citizens. In the early 2000s, Lawrence House was sold again and as the senior population dwindled the new owners partnered with social service agencies to house the mentally ill who were being driven out of institutional homes. By 2008, the building was operating as a “single room occupancy” building (SRO), housing of last resort for the Uptown’s lowest income residents.

An ad for the New Lawrence Hotel’s pool. Source: Chicago Daily Tribune

This 1929 advertisement showcases luxurious common facilities, and promises future tenants that Lawrence House is “Just like a fine club.”

Between the 1930s and 1950s, the Depression and its lingering effects ensured a large influx of job-seeking poor individuals, while the development of American suburbs led to an outmigration of the wealthier clientele to whom residential hotels like Lawrence House appealed. Chicago, like other early industrial hubs, always had SROs—such as boarding houses—to cater to a transient working class made up largely of single people. More modern SROs offer single rooms with a stove and a bed. Many larger Uptown buildings were converted into SROs— with apartments partitioned into smaller housing units, catering to the poorest of the poor. Often, these accommodations were barely habitable with poor ventilation and minimal maintenance.

As a “retirement hotel,” for many years Lawrence House was not an SRO but a luxury senior home—it only transitioned to an SRO after many years as a building for the elderly. The retirement hotel was a phenomenon during the late 1960s through the early 1980s. A few blocks away from Lawrence House, the same developer had, during the late 1960s, converted the Chelsea Hotel—another relic of Uptown’s pre-automobile boom period—into a luxury old folks home. The Chelsea Hotel would later become home to Jesus People USA, a religious communal organization that operates numerous businesses out of the hotel at 920 W. Wilson.

Wilson Men’s Hotel, a former SRO in Uptown, was known as a “cage hotel”—a common type of SRO hotel in which rented “rooms” did not have walls that went all the way to the ceiling, but instead used a “cubicle” type of format with metal wire topping the units and allowing for ventilation (this design is sometimes also used in storage units). In this image, Duane Rajkowski looks up through the wire-fencing that makes up the ceiling of his room in Wilson Men’s Hotel.

Lawrence House, 1967. Source: Chicago Department of Urban Renewal Records, Chicago Public Library.

As urban industrial work dried up in the 1960s, SROs came to be seen as attracting poverty and social misfits, making them antithetical to the idea of urban renewal. In the early 1980s, Lawrence House and other retirement hotels were becoming increasingly less profitable—in part because of cuts to federal social spending during the late Carter presidency and through the Reagan years. The hotels were sold, corners were cut, and the tenants soon came to comprise the elderly poor, who, in general, comprised around 50% of all SRO populations.

A newspaper ad for Lawrence House from 1970. Source: Chicago Tribune

This 1973 Keep Strong article talks about the elderly of Uptown demanding their part in the poor people’s movement at the time. Lawrence House was among the main hubs for the elderly in Uptown.

Watch this 1979 clip concerning the huge arson problem in Uptown during late 70s and early 80s. Many residents at the time believed that the arson was committed by landlords to collect insurance money. The arsonists targeted SRO and other large, low rent buildings. Numerous deaths occurred in the fires. From Media Burn Archive’s Guerrilla Television collections. Produced and recorded by Tony Medici and Mirko Popadic, retrieved with permission from Media Burn Archive.

SROs are a crucial form of low-income housing to any city—they keep homelessness in check and accommodate the basic right to shelter for the poorest of the poor. For organizations like Intercommunal Survival Committee (ISC) and Voice of the People in Uptown, and later, for alderwoman Helen Shiller, retaining SROs was a crucial aspect of making sure that urban renewal did not simply displace poorer residents who had the same right to benefit from development as wealthier residents.

City housing court was infamously ineffective in addressing the concerns of residents, neighbors, and community groups affected by the fires. Produced and recorded by Tony Medici and Mirko Popadic, retrieved with permission from Media Burn Archive.

Slumlord politics and arson for profit schemes affected SRO tenants the worst and Uptown was at the center of these issues. See the clips below from the February 1980 issue of Keep Strong, magazine of the ISC, where they discuss the frequent fires at the buildings of a certain group of landlords. SRO buildings like the Ellis Hotel (pictured at right) were frequent sites of these fires.

Images from the February 1980 issue of Keep Strong magazine depict their exposé targeted at an alleged arson for profit ring. Courtesy of Helen Shiller.

During the 1980s, in Uptown—and all over Chicago—SROs began disappearing more quickly as the city appealed to private developers, allowing them to “de-convert” the buildings into middle-class and luxury housing in order to attract investment. Pressures from wealthy residents’ and landlords played a major role in such decisions. In Uptown, countering community organizations’ efforts to demand more low-income housing, the Uptown Chicago Commission, which represented elite business interests in Uptown, consistently protested the “ghettoization” of Uptown. For them, more SROs and welfare agencies meant more socially marginalized individuals in their neighborhood, making it less attractive for developers. When these SROs were bought and their residents evicted, many of the low-income tenants became homeless, contributing to a country-wide crisis of urban homelessness.

One of the “cubicle” rooms rented at the former Wilson Men’s Hotel, an SRO that was converted into “micro apartments” after being sold in 2017. Listen to organizer and resident Lamont Burnett react to learning about the sale. Courtesy of DNAinfo/Block Club Chicago.

This 2008 ad signals Lawrence House’s shift from a “retirement hotel” to a “senior friendly” SRO. Source: Chicago Tribune

Around 2000, Lawrence House’s ownership changed hands. The new owners took advantage of government supportive living subsidies for residents with mental illness, while at the same time neglecting to maintain the building. The once luxurious interiors and common spaces of Lawrence House became roach- and mildew-infested. Despite severe housing code violations and utilities being cut off, the tenants stayed on, having nowhere else to go. Community organizations in Uptown had to fight many such cases where “slumlords” exploited the most desperate of tenants, and the city council shut down more and more low-income housing. These legal battles, however, only won them smaller and smaller percentages of reserved low-income housing units in new developments. Finally, in 2008, Lawrence House transitioned into a more traditional SRO—offering low cost housing to anyone who could cover the rent. The transition was likely influenced by the earlier change in ownership and the increasing demand for housing in wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

A 2012 Chicago Tribune article focuses on the story of Iris Delgado, one of Lawrence House’s residents when it was facing foreclosure:

Even when the heat and hot water were shut off during a stretch of cold weather this spring, Iris Delgado chose to stay in her modest, one-room apartment because she didn't want to leave her two pet canaries. For more than a week, Delgado buried herself under layers of blankets on her couch and walked around her one-room studio wearing two pairs of pants, three sweaters and her heavy coat. She ate dry foods and frozen dinners cooked in the microwave. When she absolutely needed hot water, she heated it in her microwave too. "I got very sick. I developed bronchitis. ... I was stuck in here for 4 days," she said. "Dealing with this stuff is a lot depressing."

For more than 12 years, Delgado has lived in Lawrence House, a troubled high-rise in Chicago's Uptown community….In May, Peoples Energy disconnected the gas to the building, leaving residents without heat and hot water for more than a week. Now, the building is in foreclosure and has been put up for sale….Because of the mounting problems and possible sale, residents like Delgado constantly worry that they could lose their homes. "Ideally we'd like to see the building repaired, improved and preserved as low-income housing," said Mary Lynch-Dungy, of the Organization of the NorthEast, who has been working to coordinate the tenants so they can have a voice in the foreclosure and sale process….Many Lawrence House residents can't afford to live elsewhere. They want to live in this particular neighborhood because of its proximity to social services and health care. Many can walk to see their therapists and doctors. "I love my apartment," Delgado said. "I don't want to move. I love the people here."

Cedar Street (Flats) properties in 2014. Source: Chicago Tribune

In 2014, despite protests, Lawrence House was purchased by Cedar Street (Flats), a private developer that also bought up several other SRO buildings in Uptown. The tenants were evicted with no arrangements made for humane relocation—with many becoming homeless and joining Uptown’s Tent City.

When Lawrence House was purchased by Cedar Street (Flats), Organization of the North East (ONE) fought with the tenants against eviction. Despite failing to preserve the building as affordable housing, ONE helped some residents find new low income lodgings, and their clash with the developer helped publicize the plight of SRO tenants in a hot real estate climate. Furthermore, ONE was able to get new legislation passed in the Chicago city council that aimed at preventing further displacement. The SRO Ordinance was adopted in 2014 and would play a critical role in future fights over SRO evictions—such as the battle for the Wilson Men’s Hotel in 2018.

A 2014 headline notes the passing of the key SRO Ordinance, a piece of legislation that aims to protect existing SROs by, among other stipulations, requiring any owner to first seek a non-profit buyer when looking to sell. Source: Chicago Tribune

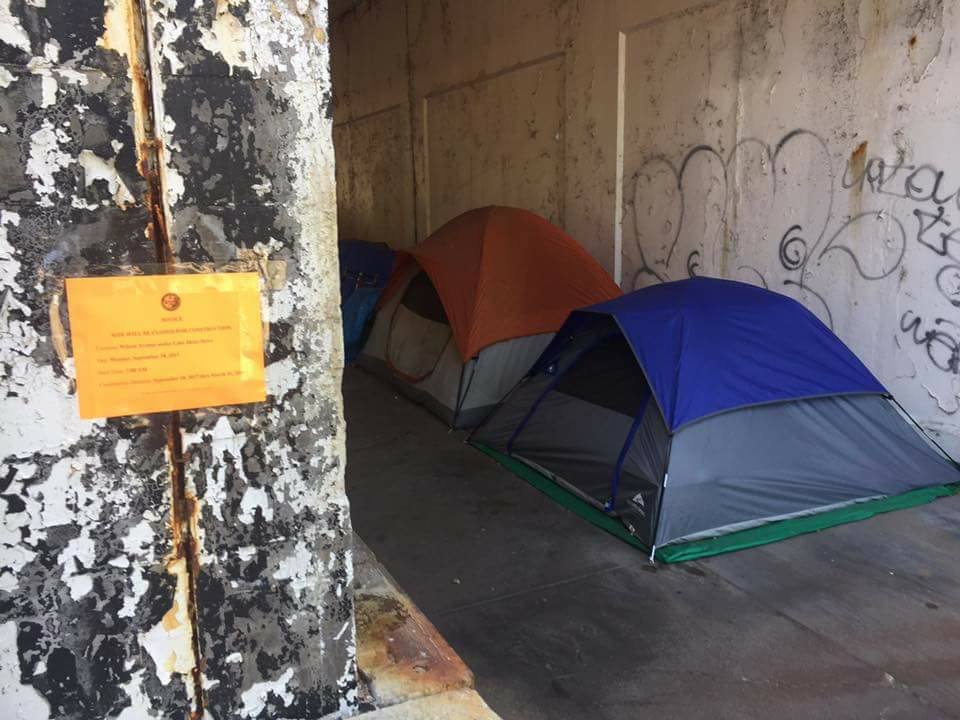

Many of those who were pushed out from Lawrence House and other SROs became part of Uptown’s Tent City, a large agglomeration of unhoused folks living in tents. Listen to Tom Gordon talk about the SRO crisis and Lawrence House. We will learn more about the Tent City struggles in our section on Uptown’s houselessness crisis.

Uptown Tent City tents with an orange city cleaning notice in the foreground. The notice details a “scheduled cleaning” of the underpass where the residents live. In such cleanings, city workers have often been indiscriminate in their treatment of Tent City residents’ belongings. Courtesy of Northside Action for Justice (facebook).

The newly revamped Lawrence House ironically pitches itself as “bringing back the Roaring Twenties,” and is touted as a great example of “historic preservation.” Once again, we face the question: what histories are deemed worth preserving, and for whose sake? Lawrence House today does not even bear a trace of the tenants who lived there for decades, fighting for the right to basic housing. While the 1920s, a decade of profound financial irresponsibility is esteemed, the lessons of subsequent eras, of the Depression and urban deindustrialization, are forgotten.

These images showcase the restored interiors of Lawrence House. Much like in the 1920s, de-converted apartments also appeal to the singles or young couples that make up a bulk of the gentrifying population in present-day cities. SRO’s are often converted to luxury “micro-units.” Source: Open House Chicago 2016

Copyright ©2018 Dis/Placements ProjectSources:

Please reach out to displacements.chicago@gmail.com for further information regarding source materials.