The First Displacements: Native Americans

The First displacement: Native Americans

Site #1 Description…

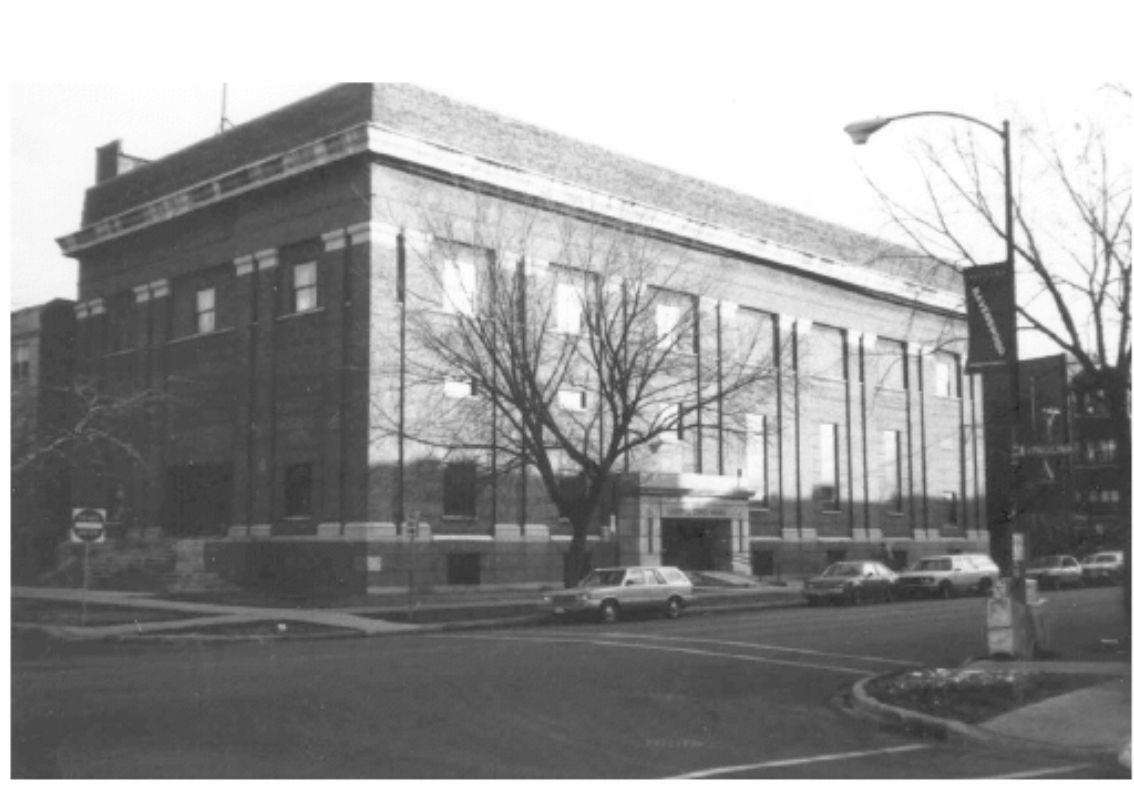

This site in Uptown (1630 W. Wilson Ave -see google map above) is where the American Indian Center used to be located until 2017.

The first displacement

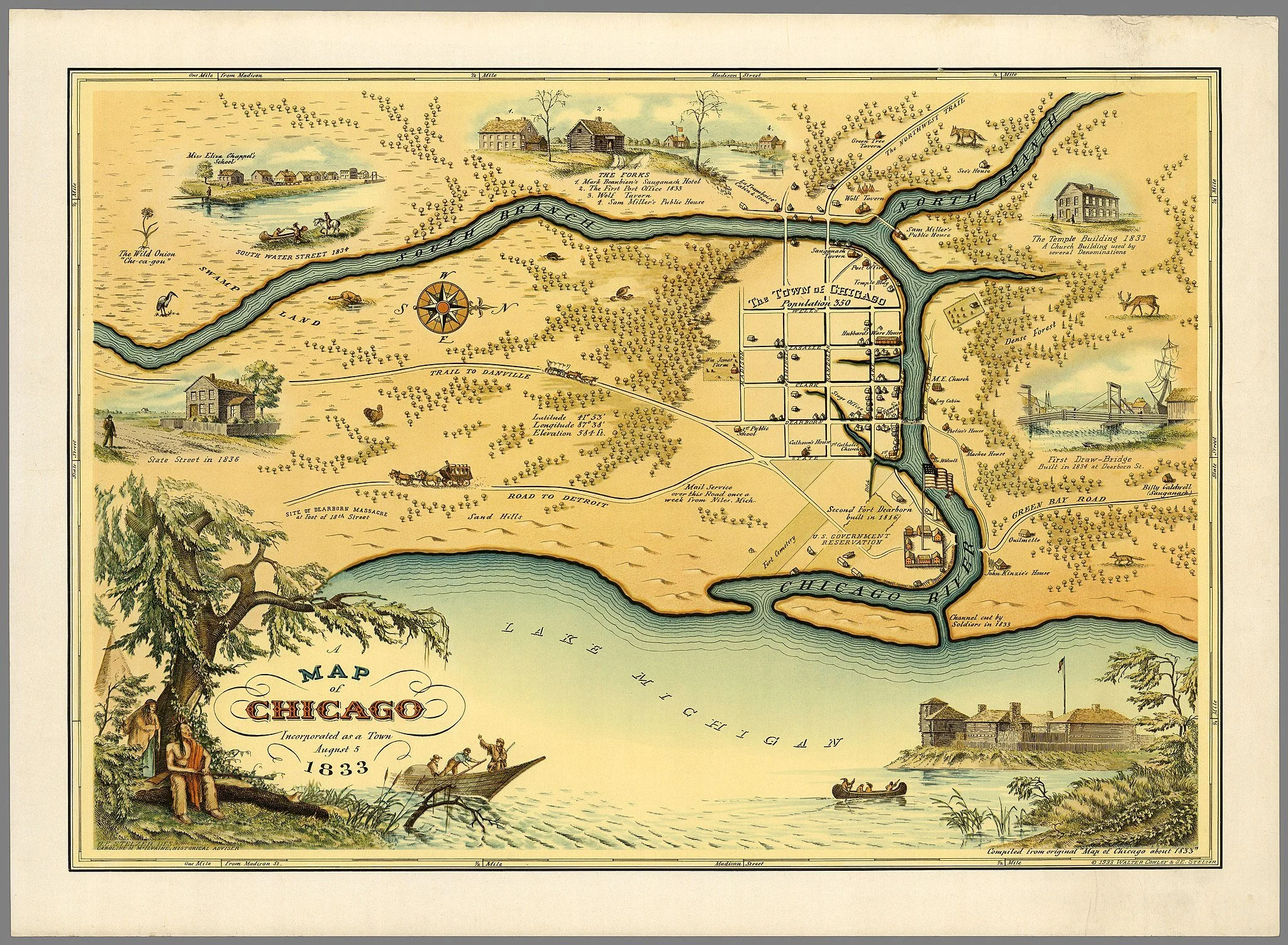

Chicago in 1833 -map by Conley and Stelzer, 1933 (WikiMedia Commons).

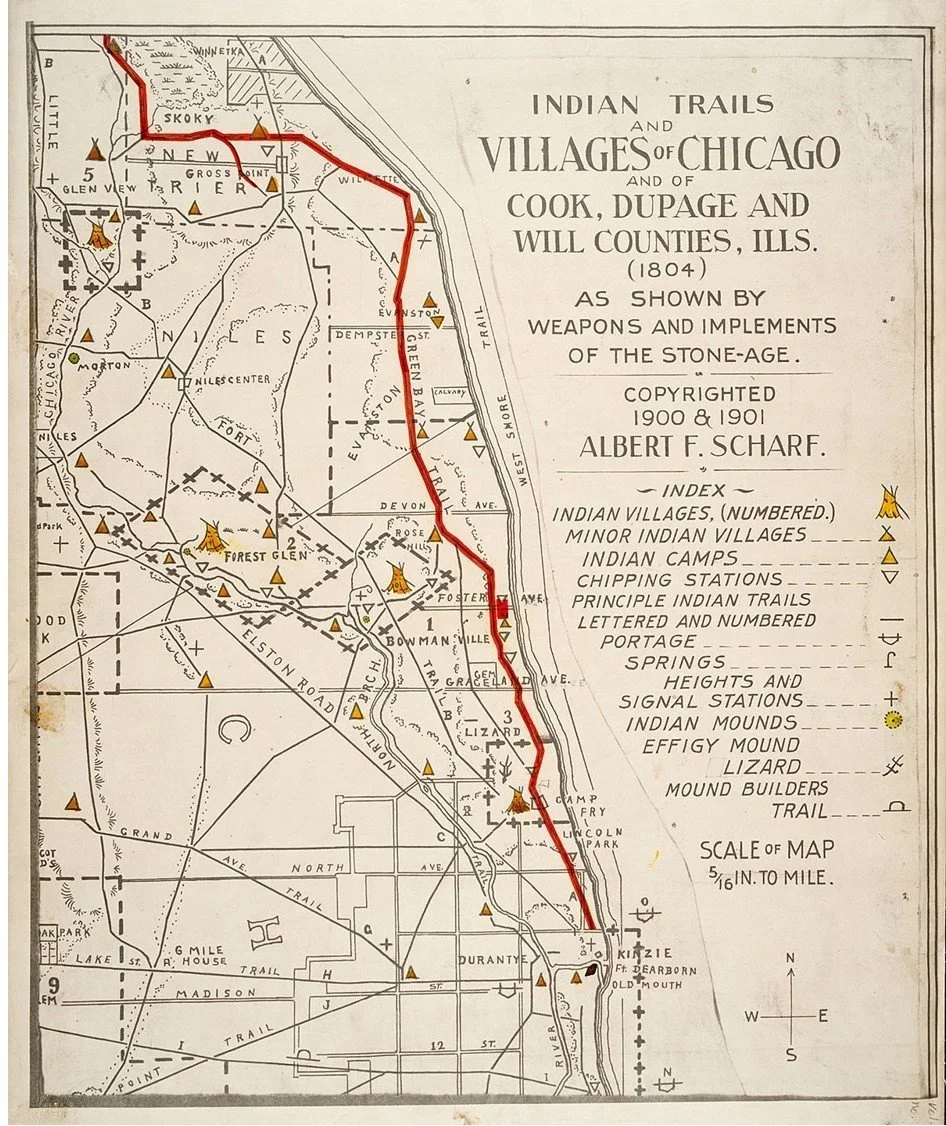

The founding displacement that shaped Chicago, and therefore Uptown, was the displacement of Native peoples from their land. Before 1833, the Chicago area was a zone of settlement, transit, and trade for many First Nations. The area of present-day Uptown was likely accessed via trails by those in nearby Podawadomi villages.

Source: Chicago History Museum

The Treaty of 1833 was the culmination of a series of laws and treaties, such as the 1816 Treaty of St. Louis, that limited Native American rights over the Chicago area, and in settled lands in general.

Photo credit: Anna Guevarra

With the founding of Chicago in 1833, the Podawadomi were moved to a reservation in Kansas by the government, though some bought the rights to stay.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

native american voices in uptown

It wouldn’t be for another hundred years that Native Americans would return to this area, when they were displaced from Midwest reservations into Chicago, and specifically the Uptown neighborhood. The federal Relocation Program of 1952 supplemented laws that dismantled Native American reservations. By the 1960s, Chicago housed one of the largest urban Native populations in the country—between 16,000 and 20,000 Native Americans affiliated with various Nations. The injustice of this displacement, and the poverty and discrimination they faced in cities, led many Native activists to speak out.

It was in this context that various Native American organizations and movements took shape in Uptown. Working with and against the establishment to varying degrees, the American Indian Center, the St. Augustine’s Center for American Indians, and the Chicago Indian Village exemplify the diversity of strategies used by Native Americans in Uptown to make their voices heard.

Betty Jack Chosa (Ojibwe), a Native American leader of Uptown in the 1970s, speaks about the predicament of resettled Native Americans. Credit (with permission): Jerry Aronson, The Divided Trail: A Native American Odyssey (film), (1978)

An older image of theAmerican Indian Center at 1630 W Wilson St.

Source: John J. Laukaitis, Community Self-Determination: American Indian Education in Chicago, 1952-2006. (Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 2015).

The American Indian Center or AIC was established in 1953 as the All-Tribes American Indian Center, the oldest urban community center for Native Americans in the US. It began as a non-Native-led endeavor to help the government (the Bureau of Indian Affairs) settle Native Americans in Chicago.

This 1956 report talks about the poor living conditions of relocated Native Americans, but also advises Indian Centers to "refrain from public controversy."

Source: La Verne Madigan, “The American Indian Relocation Progam: A Report,” (New York: The Association on American Indian Affairs, Inc., 1956), Arizona Department of Library and Archives.

However, it soon became more Native-led, breaking ties with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and defining a politics of self-determination that took a stance against government policy, reflecting the slogan of Native American mobilization all over the US: “Indians for Indians.” The AIC’s powwows remain an enduring part of its politics for pan-Indian solidarity.

American Indian Center of Chicago, Chicago’s 50 Years of Powwows, (Charleston: Arcadia, 2004).

Betty Chosa (Ojibwe) and Carol Warrington (Menominee), two leaders of the movement, recount the first major action organized by the Chicago India Village: a live-in in Wrigley Field. Credit (with permission): Jerry Aronson, The Divided Trail: A Native American Odyssey (film), (1978)

As narrated by its leader Mike Chosa (Ojibwe), the CIV soon scaled up its protest to a standoff against the Federal government. They took over the abandoned nuclear missile site at Belmont Harbor, demanding land rights and housing rights. The National Guard eventually forced the CIV to surrender, and their demands were not honored. Credit (with permission): Jerry Aronson, The Divided Trail: A Native American Odyssey (film), (1978)

The AIC also provided early support for another movement with which it eventually broke off—the short-lived Chicago Indian Village (CIV). The CIV’s politics was markedly different from that of the AIC—it focused on direct action, pressure tactics, and militancy. Its strategy of staging “live-ins” on federal land was similar to that of another iconic Red Power movement at the time, the occupation of Alcatraz island by Indians of All Tribes.

Yet another major organization is the St. Augustine’s Center set up by the Episcopalian Church in the 1950s. In marked contrast to the long history of settler missionary efforts aiming to "civilize" the American Indian, the Center actively invested in fostering Native American culture and consciousness through its educational support programs. Today, most of Uptown’s Native American families have moved out owing largely to the pressures of gentrification, but Uptown continues to be home to at least a few hundred Indigenous Americans, many of whom struggle with povertyand sustenance, remaining among the worst-affected of Uptown’s racialized groups. In 2017, the AIC announced that it was leaving Uptown and moving to Albany Park, with some of its oldest members expressing sadness over the move as an effect of gentrification in Uptown.

Copyright ©2018 Dis/Placements Project