Unhoused

Unhoused

Site #7 Description…

In this section of our tour we will look at multiple sites related to the history of unhoused persons in Uptown. Each of these locations were or are the sites of movements resisting those forces which contribute to the crisis of housing security. Common themes in the history of houselessness in Uptown since the 1960s are poverty, gentrification, and a reduction of state services. Poverty in the US is closely linked to structural racism and disproportionately affects African American and Native communities–the same communities which are at greatest risk of being unhoused. Gentrification describes many related processes, in the case of houselessness in Uptown the most critical aspect of gentrification is the reduction of available affordable housing and blockage of new construction of low-cost accommodations. Developers and wealthier, more recent arrivals to Uptown have made concerted efforts to limit cheap housing in the neighborhood, diminishing the options available to those experiencing houselessness or at risk of being unhoused. In addition to gentrification, state-led actions to rollback mental health services have been central in the long crisis of homelessness. These moves include the poorly executed strategy of deinstitutionalization of the latter half of the twentieth century as well as more recent efforts to drastically reduce the state- and city-funded mental health clinics that provide at-risk individuals with the resources they need to attain secure housing.

This clipping from Keep Strong magazine, June 1980 highlights the housing struggles of one Appalachian family who fell in and out of homelessness following a tragic car accident.

A man sits in a chair at the 4425 North Malden empty lot where a 1988 occupation by Chicago-Gary Union of the Homeless took place (Photo by Phil Greer for the Chicago Tribune, October 11, 1988).

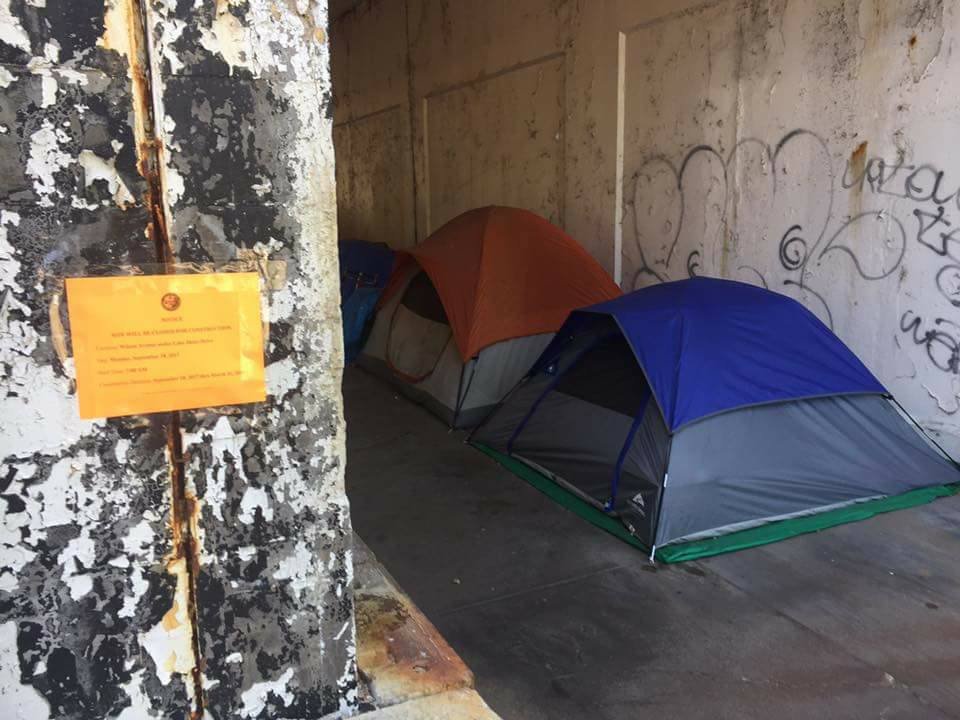

This photo, courtesy of Northside Action for Justice, shows tents under an Uptown underpass, with a city cleaning notice in the foreground. Tent city residents often face harassment by city officials in the form of frequent, unscheduled cleanings of the underpasses.

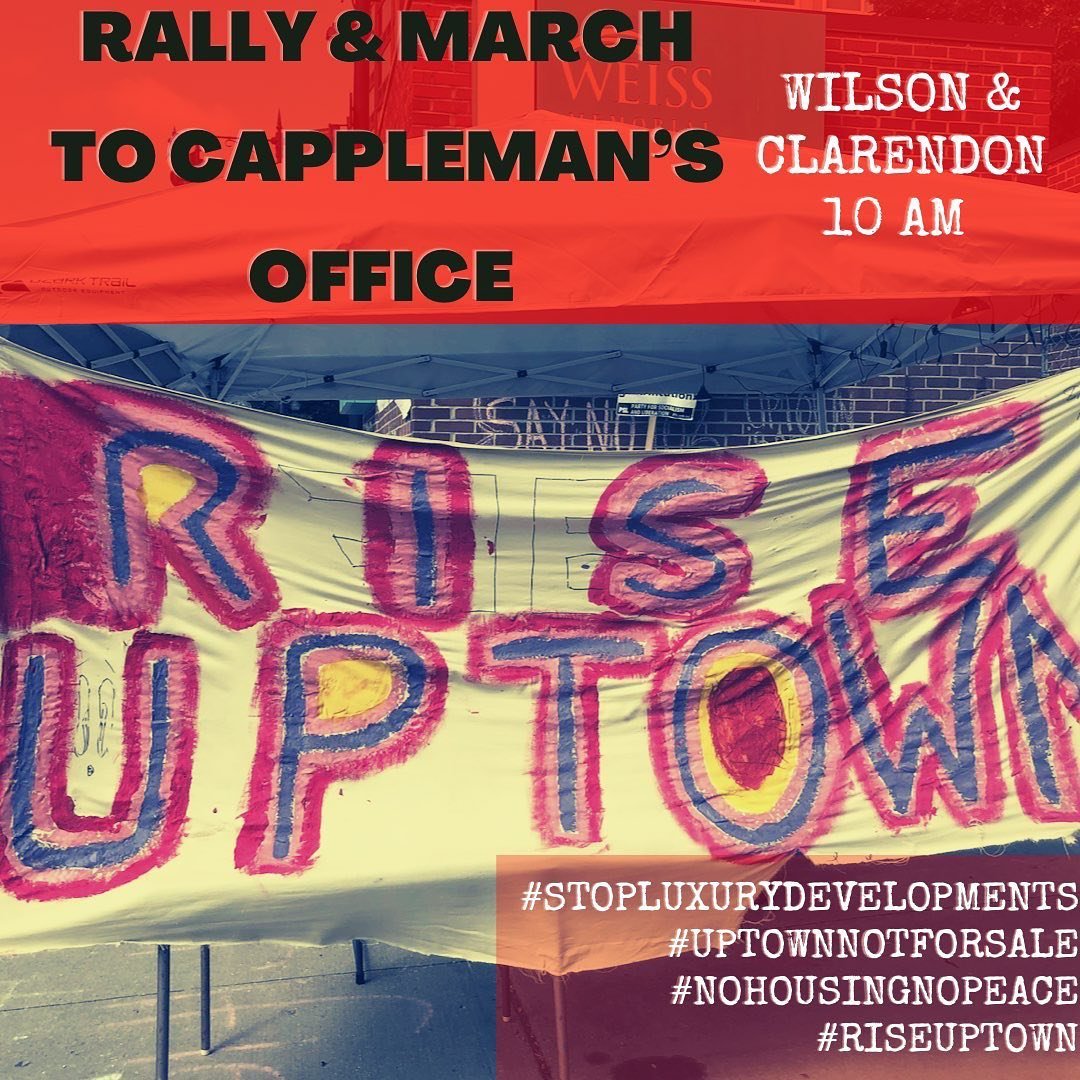

A social media flyer circulated by local Uptown affordable housing organizers in response to the sale and planned luxury re-development of Weiss Hospital’s parking lot. Source: facebook.com/displacementsproject

Mike Chosa of Chicago Indian Village (CIV) meets with the Chicago Presbytery in 1971 to request that the latter offer a loan to CIV to help improve housing and schools for Native families and children in Chicago. Chosa drew on the role of American Presbyterians in the founding and running of infamous “Indian schools” to make a case for the Chicago chapter to loan Chicago’s Native population funds. Photo by Larry Graff for the Chicago Sun Times. Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum.

In spite of the powerful forces which have exacerbated issues of houselessness in Uptown for decades, throughout this time various groups have banded together to resist these processes. Many times these resistance actions have taken the form of strategic occupations. This is true in the case of the efforts of the Chicago Indian Village (CIV), a radical native rights organization. CIV emerged in the context of the militant civil rights groups of the early 1970s and in response to federal, state, and local policies of Native erasure. During a period of Native American history known as the “Termination Era,” Through a series of acts between 1952 and 1956 the US government stripped Native reservation land of federal protection, offered it up for private sale, and simultaneously coerced and incentivised Native people to move to cities. In the subsequent decades Native Americans urbanized at higher rates than any other demographic group in the United States. Chicago’s Native population increased twenty-fold during this period, making it one of the most important national urban centers for Native people. In 1962, approximately 49% of Native Americans in Chicago were living in Uptown. Unfortunately, like their Appalachian neighbors, Native refugees faced not only severe material privation but also housing discrimination upon arriving in Chicago, making them especially vulnerable to the condition of houselessness.

The eviction of Carol Warrington, a Native mother-of-six, and her family from their apartment next to Wrigley Field, led to the foundation of CIV when she and others decided to camp on a series of vacant lots adjacent to the ballpark. CIV was active in Chicago in the early 1970s and became well known for a series of strategic and practical occupations. These well-publicized occupations were part of an effort to both directly combat the immediate issue of housing insecurity while also drawing attention to CIV’s larger goals of establishing Native schools and permanent housing. In late 1970, seeking emergency relief for nine Native families, CIV occupied 1142 West Ainslie, a 15-unit condemned apartment building in Uptown. In spite of the building’s shortcomings–it was dilapidated and initially lacking heat–the group pursued its purchase. However, CIV was unable to secure the appropriate funds to buy it before a fire broke out, forcing the group to relocate. 1142 West Ainslie was demolished and a parking lot has since taken its place.

This leaflet from the 1970 occupation shows how CIV’s actions were coordinated with the Young Patriots, the Appalachian-rooted group fighting for Uptown’s poor whites, and exemplifies the coalition-driven radical organizing of the early 1970s. The 4901-4909 Broadway address listed in the pamphlet is in reference to the same 1142 Ainslie building which was on the corner of Broadway and Ainslie, across the street from the historic Uptown Service Station car wash. Courtesy of Peggy Terry Archives of Wisconsin Historical Society.

When the Community Mental Health Act of 1963 was passed many state-run institutions for the mentally ill were shuttered in response to growing criticisms of these institutions and as a strategy to cut costs. These institutions were rife with ethical violations and many favored a move towards a new community-based care model. However, the shift from an institutional model to a community one was executed abysmally, often leaving patients high and dry. Uptown, with its numerous options for cheap housing in the late 1960s, was the location where many residents of state-run hospitals were discharged. Significant numbers of former patients found homes in the neighborhood's cheap SRO hotels, of which there were still a good number at the time. SRO hotels were originally developed to house single workers while they saved for apartments, but as housing became more scarce during urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s, many low-income residents sought out SROs as permanent affordable housing.

Lawrence House, formerly “The New Lawrence Apartment Hotel,” in 1981. Around the time of World War II the building became an SRO to cater to Chicago’s swelling war-time labor force Photo: C. William Brubaker Collection (University of Illinois Chicago)

The Bachelor Hotel, an SRO on Wilson Avenue, as photographed in 1975. This SRO was converted into market-rate apartments after former owner sold the building to major private development group Cedar Street (Flats Chicago). The building was sold and redeveloped 10 years after the owner used city grant money from the SRO Refi Rehab program to update it. Photo: C. William Brubaker Collection (University of Illinois Chicago)

Wilson Men’s Hotel in 1975, seen from under the Red Line tracks. The former SRO was recently rehabbed and refashioned into 76 “micro apartments” by the development group City Pads after they purchased the building in 2018. Most of these apartments are listed at market rate. A significant portion were set aside for low income renters but for how long is unclear. As of 2022, the building—now marketed as “The Wilson Club” (a nod to a past name, as seen in the photo)—is for sale again, with an asking price of nearly 13 million dollars. Photo: C. William Brubaker Collection (University of Illinois Chicago)

From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, Chicago lost over 17,000 SRO units, mostly from the near west side. In the subsequent decades, the relatively high number of SROs remaining in Uptown would continue to shrink, in spite of efforts by various nonprofit groups and some private owners to preserve them. These closures led to a spike in the number of unhoused people in the neighborhood. Lakefront SRO was one of a number of local non-profits making efforts to combat houselessness by rehabilitating and preserving SRO housing in the face of gentrification. Lakefront SRO was later subsumed into Mercy Housing, a national nonprofit that continues to purchase and maintain affordable and supportive housing in the neighborhood. As we will see, others resisted the changes by making a claim on the Chicago Housing Authority’s promise of new public housing.

Headlines from the Chicago Tribune (late-80s, early-90s).

This 1990 community fact sheet shows the loss of over 1,000 housing units in Uptown during the 1980s, along with other data points that indicate shrinking housing options for the poor—such as the neighborhood’s loss of over 600 SRO units between 1973 and 1990. Source: Chicago Rehab Network 1990 Fact Sheet. Courtesy of Chicago Rehab Network.

During the 1980s, gentrification was sapping naturally-occurring affordable housing from Uptown and the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) was failing in its rollout of new scattered site public housing. To make matters worse, more and more existing public housing was being decommissioned because the CHA had failed to maintain its properties. All of these factors combined to exacerbate the crisis of houselessness in Uptown, and in October of 1988, community organizers took a stand. A coalition of the neighborhood’s unhoused and advocates for the houseless came together to protest the city’s failure to retain, maintain, and produce affordable housing. Together they cut the lock to an empty CHA-owned lot at 4425 North Malden, pitched tents, and demanded a plan of action to build scattered site housing at the site. Listen to Marc Kaplan, who participated in the occupation, describe how it came together.

Marc Kaplan, a longtime organizer for affordable housing in Uptown and a co-founder of the local group Northside Action for Justice (NA4J).

Helen Shiller, the brand new alder of Chicago’s 46th Ward, is arrested at the Tent City protest in 1988 (Photo courtesy of Depaul Digication Uptown Community Tour).

Headline clippings from Chicago Tribune, October 1988.

An image from Chicago Rehab Network’s May/June 1988 newsletter. The image shows a tent city encampment organized by Chicago/Gary Union of the Homeless. This tent city was likely erected on the Near West Side, where the Union of the Homeless was quite active due to serious displacement of SRO residents during the 1980s. Photo by Debbie Weiner, courtesy of Chicago Rehab Network.

At the core of the protest was the Chicago/Gary Union of the Homeless, an organization made up of houseless families and individuals, and members of the Anti-Displacement Coalition, a group made up of members of different local community organizations. Though the demonstrators were cleared out and a few even arrested, the occupation was ultimately successful and scattered site housing was built on the lot which remains in Uptown’s affordable housing profile to this day. The Malden lot tent city presaged the strategy and struggles of Uptown’s contemporary Tent City at the neighborhood’s eastern edge.

“What we did was when we were forced to vacate the property, we got into buses and we all went down to the HUD office… and said, kinda said ‘if we can’t live over there we’re gonna occupy this space until you agree to build some scattered site housing there [in Uptown]’” -Marc Kaplan on the occupation and subsequent protest

First photo: Lawrence Avenue Lakeshore Drive viaduct in 1938 (Courtesy of UIC Special Collections: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Traffic photographs). Second photo: Tent City encampment along Wilson Avenue adjacent to the viaduct. Third photo: Tom Gordon, a prominent leader in the Uptown Tent City community.

Today’s Uptown Tent City has primarily occupied the Lawrence and Wilson viaducts at Lakeshore Drive, though it has at times been displaced or moved voluntarily. The encampment was formed in the 2010s and is a practical occupation in response to the shrinking availability of affordable housing in Uptown. The organization by unhoused people into tent city communities emerged as a way to improve the safety of the houseless individuals and has also served as a way of establishing collective political strength.

Uptown Tent City has its own rules–mainly used to discourage theft and violence–and its residents receive support from local community groups and churches in the form of blankets, tents, and food. Unfortunately, the residents of Uptown Tent City have suffered harassment at the hands of the Chicago Police Department and Chicago Park District, often being uprooted unlawfully for irregular cleanings or maintenance. The emergence of Tent City in the 2010s appears to be in direct conjunction with the closure of numerous SRO hotels in the Uptown neighborhood in that decade. Institutions like the Lorali, Wilson Men’s Hotel, Lawrence House, and the Darlington Hotel all closed in the decade, drastically reducing the neighborhood’s table of affordable housing. All of these buildings were converted into market-rate developments with few if any affordable units.

A map showing the decline of SROs in Chicago in recent decades (Uptown is outlined in red). Courtesy of Ryan A. Fulgham “Where Have They Gone? Examining the Success of Chicago’s SRO Preservation Ordinance” (University of Illinois Chicago Institute for Policy and Civic Engagement, 2020)

In January of 2021 Weiss Hospital entered into a contract to sell the hospital’s parking lot to a luxury developer. Local community organizers and activists immediately spoke out against the sale, recognizing the importance of affordable development and the risk that losing the lot posed to the hospital’s future moving forward. Throughout 2021, Northside Action for Justice (NA4J) organized fundraisers and circled a petition to raise awareness about the threat of the development and prepare the community to fight the project. In the summer of 2022, a strategic occupation at 4600 N Marine Drive–in the Weiss Hospital parking lot–was organized by members of the Rise Uptown Coalition–a group made up of members of the Chicago Union of the Homeless, NA4J, ONE Northside, and Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAAJ), among many others.

Singer Adam Gottlieb leads protestors at the #RiseUptown encampment. Courtesy of Anna Guevarra.

Local musician and activist Adam Gottlieb sings the song that he wrote and recorded for the #RiseUptown occupation. Courtesy of Adam Gottlieb (https://www.patreon.com/adamgottliebandonelove)

A social media informational piece breaking down the proposed housing development at 4600 N. Marine Drive. Source: facebook.com/displacementsproject

The lot was sold to developer Lincoln Properties in a controversial deal that divided the local community board. Lincoln Properties’ plan included only eight affordable units, less than 3% of the total 314 units and less than the 10% affordable required at the time (now up to 20%). In spite of this, the plan was approved because of a loophole which allowed developers to pay “in-lieu” fees to avoid up to 75% of their affordable requirements (now 50%). Together they protested the planned luxury development which would provide little affordable accommodations and would contribute to rising rents and shrinking low-cost options. Furthermore, the sale and redevelopment of the Weiss’ parking lot has sparked fears in some Uptown residents that the hospital will soon follow. This fear is substantiated by the fact that Weiss hospital was in fact sold to a new owner, Resilience Healthcare in 2022. While Weiss’ new owners claim they have no plans of closing the hospital, the sale creates uncertainty and some worry about the hospital’s future.

Located just hundreds of feet from the Wilson viaduct Tent City, Weiss plays a critical role in the safety of Uptown’s unhoused. Losing the hospital would be a blow to the houseless community of Uptown and would continue the troubling trend of reduction of mental and physical health services in the city’s neediest areas.

In 2022, The Chicago Coalition for the Homeless released a report showing that their estimate of people experiencing homelessness in Chicago had risen from 65,611 in 2020 to 68,440 in 2021. The Chicago Union of the Homeless has attempted to address the issue by demanding that the Chicago Housing Authority immediately fill unoccupied CHA units with unhoused people and release CHA funds and vouchers to be used for finding housing for those experiencing homelessness.

A call to action circulated by Northside Action for Justice during the Weiss Hospital occupation. The social media post asks Rise Uptown Coalition to march to the alderman’s office in response to efforts by Cappleman and others to push the development at 4600 N. Marine Drive through.

On September 14th, 2023 Mayor Brandon Johnson introduced to the city council a tax plan, known as “Bring Chicago Home,” that would increase real estate transfer taxes on homes sold for more than 1 million dollars and put the resulting revenue towards combating houselessness and expanding affordable housing. The mayor had campaigned on this plan, which has been advocated by progressives for years. The proposal came as the city struggles to address a large influx of asylum seekers. In the fall of 2023, the original proposal was revised to include a reduction in tax on the sale of homes under 1 million (.6% down from .75%) and a graduated increase for those worth over 1 million—2% for those between 1 and 1.5 million and 3% for those selling for more than 1.5 million. The revised plan was scheduled to go before votes in a March 2024 referendum.

Real estate interests, led by the Building Owners and Managers Association of Chicago (BOMA), lobbied for months against the proposal, hoping to paint it as a broad property tax increase—in spite of the fact that the proposal was not a property tax (it proposed a real estate transfer tax) and it was estimated that the measure would lower transfer fees paid by the vast majority of sellers. Before voting in the election began, BOMA and other real estate groups brought a lawsuit against the Chicago Board of Election Commissioners claiming that the Bring Chicago Home proposal was employing a prohibited legal tactic of “logrolling.” In February, after voting had begun, Cook County Circuit Judge Kathleen Burke sided with the industry in the case, invalidating the referendum in an opaque decision which cited unreleased court records. After the Chicago Board of Elections appealed, Judge Raymond Mitchell reversed Burke’s decision on March 6, allowing the question to remain on the March ballot. Ultimately, the measure failed to pass, unable to survive the combined challenges of legal uncertainty and historically low voter turnout in an election that lacked a significant local race and which included an uncontested yet controversial Democratic Presidential primary candidate in Joe Biden.

Resources for persons experiencing houselessness

Many Uptowners continue to experience houselessness. Chicago Union of the Homeless is a group focused on engaing in direct action and advocacy for Chicago’s houseless—the group is also run by many folks who have experienced homelessness. Chicago’s Coalition for the Homeless serves the city’s unhoused persons through advocacy, outreach, and direct service–they are an excellent resource for anyone experiencing houselessness. Chicago’s Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS) is responsible for providing aid to the city’s unhoused persons, here is a link to a list of their programs (homeless services begin on page 2). Other groups that serve the community in the Uptown area include Mercy Housing, Sarah’s Circle (women only), Northside Action for Justice (NA4J), Jesus People USA, and Voice of the People (VOICE).

https://www.bringchicagohome.org/

Copyright 2018 Dis/Placements Project

Sources:

Please reach out to displacements.chicago@gmail.com for further information regarding source materials.