Lakeview Towers (Copy)

Wilson Men’s Hotel

Site Description…

Wilson Men’s Hotel was an SRO located at 1124 W. Wilson Avenue, a couple of doors west of the Wilson Red Line station. It has been known by many names through the years, including the Wilson Club Hotel, the Wilson Men’s Club Hotel, the Wilson Men’s Hotel, and finally, following its sale and conversion to mostly market-rate units, the Wilson Club. Wilson Men’s operated for almost a century as one of the cheapest types of urban housing available—a cubicle hotel—where residents occupied tiny rooms on large, subdivided floors with shared amenities. In 2017, the building was sold to the developer City Pads, and a fight to ensure the fair treatment of its nearly two hundred tenants ensued. As we will see, the tenants won significant gains, helped by local organizers at ONE Northside, but were ultimately displaced, with many joining Uptown’s growing unhoused community. The fight for Wilson Men’s Hotel and its residents reveals both the massive challenges and ultimate possibilities inherent in the effort to preserve SROs. Tenants and local organizers both stepped up to preserve the dignity and safety of the Wilson Men’s residents, creating a moment where the future of SROs mattered in Uptown during a period when real estate capital was squeezing them out of the neighborhood.

The dry goods and department store that predated Wilson Men’s Hotel can be seen on the right in this photo from 1914. Source: DN-0063227, Chicago Daily News Collection, Chicago History Museum

This 1968 photo shows the Wilson Men’s Hotel in the center-left of the image. The Bachelor Hotel, another SRO, is the the foreground. Source: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-074023; Sigmund J. Osty, photographer

Establishments like the Wilson Men’s Hotel faced opposition from neighbors from the beginning. Often, more affluent residents of the area looked down on the tenants of SROs and fought to prevent the building of this type of housing.

The building that housed the Wilson Men’s Hotel was completed in 1914 and operated as a department store in its early years. In 1929, following the stock market crash, the building was sold to SRO developer Jacob Marks who outfitted it as a “cubicle hotel,” with each of its three residential floors partitioned into approximately 100 7x7 units topped with wire “ceilings.” The local neighborhood group Central Uptown Association (CUA) fought the building’s conversion, derisively calling it a “flophouse.” However, once the Depression set in, the CUA’s bourgeois resistance had to surrender to the obvious need for cheap housing, and the Wilson Men’s Hotel opened its doors soon after the renovation.

The SRO served a steady clientele of low income workers throughout the Depression and into the New Deal era of the late 1930s and 1940s. However, Wilson Men’s Hotel, likely prompted by the racially restrictive covenant set in motion by the CUA and local property owners, excluded African Americans from its beginnings into the 1970s. By the 1950s and 1960s, numerous factors, including White flight, corporate suburbanization, and deinstitutionalization had reshaped the fabric of the Uptown neighborhood. SROs continued to play an important role in providing affordable housing during this period, however, as the city’s tax base fled to suburbs. These hotels, which had once serving as temporary lodgings for newly arrived workers, became a preferred option for Uptown’s desperately poor, disabled, and elderly residents.

The Wilson Men’s Hotel, as the only cubicle SRO in the neighborhood, offered the cheapest rents and afforded the neighborhood’s most destitute residents a more dignified existence than the alternative, houselessness. With approximately 250 rooms for rent, this mid-sized building was overcrowded and the conditions were often deplorable, but, in spite of the poor conditions, residents often spoke about the importance of having a place of their own. The Wilson Men’s Hotel offered a space of relative safety and dignity when many tenant’s only other option was sleeping outside. In fact, many poor men who couldn’t work often split their time between the hotel and the streets, spending what money they had to stay a few nights a week in the building’s cubicle rooms while roughing it unhoused the rest of the days.

"Most of the people here, we've been on the streets. We don't want to be around that. So we come to this place, this haven."

-resident Charlie P. speaking to the Chicago Tribune in 1993

A 1946 advertisement in the Chicago Daily News for the job of night shift porter at the Wilson Men’s Hotel. The advert reveals that the owners of the Wilson Men’s Hotel sought to employ Black worker even as they barred Black tenants from the SRO in its early decades.

This 1930 advert in the Chicago Daily News implored men to “economize” their lodgings and lists the Wilson Club Hotel at the top of Marks and Co.’s large capacity SRO offerings. The other two hotels were located on the Near West Side, an area that served as a migrant hub in late 19th and early 20th century Chicago before significant urban renewal projects like construction of the Congress (now Eisenhower) Expressway and the building of University of Illinois at Chicago Circle (now UIC) displaced many low income residents.

1981 Nathaniel Burkins Argument Wilson Club Men's Hotel

Wilson Men’s Hotel survived the early gentrification wave of the 1980s, when many other SROs in the city were bought up, closed down, and converted into market-rate housing. However, in 2013, Wilson Men’s Hotel came under threat again from the relatively new 46th Ward alderman James Cappleman. Cappleman and alderman of the 42nd Ward Brendan Reilly had cosponsored an ordinance which would ban cubicle-style SROs from the city. The ordinance failed, but the alderman and others in Uptown would continue to try to reshape the neighborhood’s character by encouraging real estate development and targeting poor people’s services. For example, Cappleman threatened the license of the Salvation Army soup truck that visited the neighborhood regularly to give out hot meals to Uptown’s most destitute residents.

Lamont Burnett lived in the Wilson Men’s Hotel for 13 years before its sale to City Pads in 2018. Listen to the clip below where Lamont talks about the Wilson Men’s before the sale.

One of the rooms rented at the former Wilson Men’s Hotel before it was converted into “micro apartments” following the 2017 sale. Courtesy of DNAinfo/Block Club Chicago.

In the summer of 2017, Wilson Men’s Hotel was sold to developer City Pads. City Pads was looking to remove residents quickly, renovate the building, and reopen it as a market-rate lodgings for young professionals. The sale of this long standing institution of affordable housing reopened the wounds of the Lawrence House sale and sparked a resistance effort spearheaded by tenants and, as in the case of Lawrence House, ONE Northside. In 2016, the city recorded a 9.4% rise in homelessness in Uptown—in large part the result of the recent closings of SROs like Lawrence House, the Norman Hotel, and the Hazelton Hotel (the latter also purchased by City Pads).

Listen to organizer and resident Lamont Burnett talk about his reaction to learning about the sale.

This image shows one of the Wilson Men’s Hotel’s tenant press conference demonstrations. Residents hold up signs that say “Indoors in Uptown” and others that indicate the length of their stay in the SRO. These actions helped the movement gain traction in the press and show locals that Wilson Men’s residents weren’t necessarily transient—some had been staying in the hotel for over a decade. Photo by Stephen Gossett, courtesy of Chicagoist.

Tenants organized press conferences on the sidewalk in front of the building, just steps from the busy Wilson El station. These actions gave the residents of Wilson Men’s Hotel visibility, attracted press coverage, and empowered residents to work together to resist eviction. Tenant’s demonstrations also caught the eye of city officials who began investigating whether the developer City Pads was complying with the 2014 SRO Preservation Ordinance.

Listen to Noah Moskowitz explain the importance of the 2014 SRO Ordinance in the context of a new wave of real estate development. Moskowitz worked as a housing organizer with ONE Northside and helped organize Wilson Men’s tenants in 2017 and 2018.

The gains that tenants and ONE Northside had won in the fallout of the Lawrence House fight, namely, the passing of the SRO Preservation Ordinance in 2014, equipped organizers with new tools to fight evictions and displacement. The ordinance requires owners who are looking to sell SRO properties to hear out offers from non-profit buyers for 180 days before discussing a deal with for-profit developers. The ordinance was passed along with a funding package, but by 2017 those funds had dried up, making it hard for non-profit developers to offer cash up-front to an SRO seller and incentivizing sellers to consider a for-profit buyer. Non-profit developer Interfaith Housing made a bid to buy Wilson Men’s Hotel, but the owner didn’t want to wait for the preservation organization to raise the funds.

The SRO Ordinance also contained stipulations for rehousing residents of SROs who would be displaced by a sale, including $2000 for each resident who would not be offered a space in the new development. City Pads’ “transition team” was not up to the task of relocating tenants. During the fall of 2017, organizers at ONE Northside worked with Wilson Men’s residents to find them new affordable lodgings and avoid becoming unhoused. Residents and ONE Northside also worked together to form a tenants association—listen to Noah Moskowitz detail the grassroots nature of this organization.

Wilson Men’s Hotel resident Eric Holmes Sr. worked in a kitchen. Noah Moskowitz describes how Holmes’ regular contributions of food leftover from his job helped bring residents together and form a tenants association.

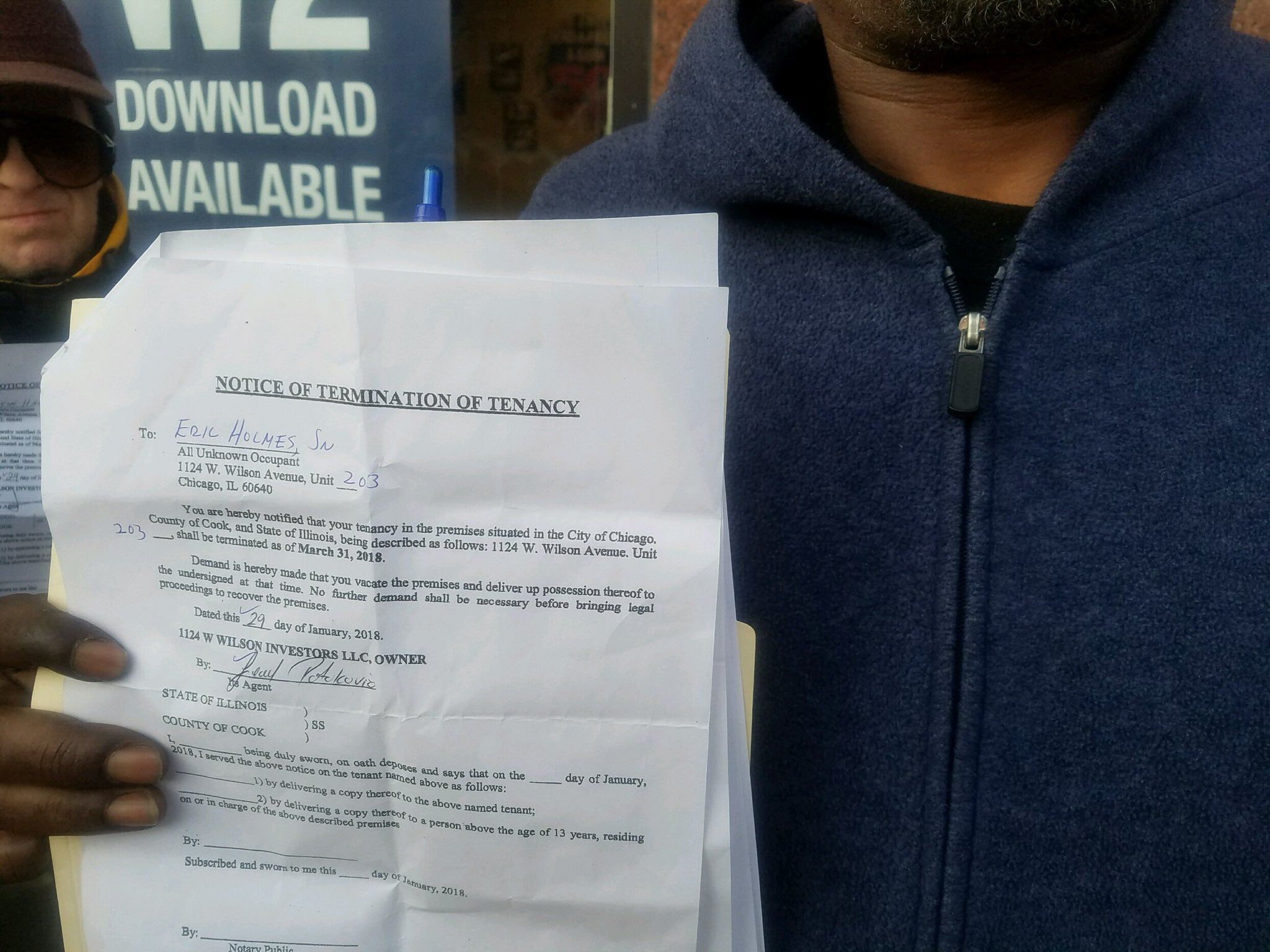

Eric Holmes Sr. displays his eviction notice from City Pads (1124 W Wilson Investors LLC). Holmes made the front page of the Chicago Tribune in January 2018 when he spoke about the concerns of residents facing eviction. Courtesy of ONE Northside.

The tenor of the struggle changed in the first few weeks of 2018. Residents, experiencing utilities failures, reported their grievances to the city, sparking what some saw as a retaliatory response from the developer—60 day evictions notices. The reply from residents and the city was swift—the city threatened to sue City Pads for violating the SRO Ordinance, specifically the law’s requirements for an explicit rehousing plan and for details about how a proportion of tenants might return to live in the renovated building’s mandated affordable units. The city’s Planning and Development Commissioner David Reifman addressed City Pads’ actions in a letter to the developer in late January, 2018: “Your disregard for the requirements set forth in the SRO Preservation Ordinance, combined with your recent distribution of Notices, undermines the spirit of the ordinance and puts these vulnerable tenants at risk for homelessness.” In February of 2018, the tenants association issued a press release in response to City Pads’ eviction notice.

The complaints about issues with the building’s heating and water systems landed Wilson Men’s Hotel in building court, and in March of 2018 the city issued an injunction barring City Pads from evicting residents until a hearing scheduled for the first of May. Residents, assisted by the Shiver Center on Poverty Law, petitioned to join the court case against City Pads, alleging that the developer had retaliated against their reporting of the conditions of the building with eviction notices. Wilson Men’s tenants packed the courthouse, protesting their treatment at the hands of the developer and demanding that the company comply with the SRO Ordinance.

In February of 2018, residents of Wilson Men’s Hotel deliver their statement demanding City Pads comply with the rules of the SRO Ordinance. The tenants association also pressured the city to hold City Pads accountable for its actions. Courtesy of ONE Northside.

Ultimately, residents were able to negotiate a settlement that promised relocation funds for tenants who would not be offered a spot in the renovated Wilson Club. Of Wilson Men’s Hotel’s approximately 120 residents at the time of the sale, only two were able to ultimately return after renovations. The new Wilson Club has 24 units set aside as affordable housing, but the cost to rent many of these units, while considered affordable by some measures, is often still out of reach for former SRO tenants. Some of the building’s former tenants, particularly those who were willing to work with ONE Northside, were able to find temporary or permanent low cost housing at other SROs. But the reality that many former residents faced—removed from their home and with affordable housing options like SROs becoming increasingly scarce—was houselessness. In August of 2018 the last Wilson Men’s Hotel tenants were forced out of the building. The fight for Wilson Men’s Hotel should be seen as a victory: residents were able to delay eviction for almost an entire year and they won an unprecedented settlement—showing that SRO tenants could effectively pressure the city to enforce the 2014 ordinance. However, the fact remains that not enough is being done to protect these buildings and their residents from development that displaces and unhouses the city’s most vulnerable citizens.

Organizer and current Wilson Club resident Lamont Burnett reflects on what became of Wilson Men’s Hotel tenants after the sale.

Copyright ©2018 Dis/Placements ProjectSources:

Please reach out to displacements.chicago@gmail.com for further information regarding source materials.