Resisting Urban Removal

Resisting urban removal

Site #7 description…

The site marked on the Google map above is Lawrence House, a Single-Room Occupancy (SRO) building that served poor and working-class residents of Uptown and was converted into a luxury apartment building in 2014 by the "Flats" developer, Cedar Street Company.

Uptown's racial diversity and affordability for poor people has been under attack for decades. That Uptown remains one of the few lake-adjacent northside neighborhoods that are racially diverse and mixed-income is testimony to the remarkable struggles around affordable housing across these decades.

An old postcard depicting Lawrence Hotel, a building since "developed" by Flats LLC into luxury Lawrence House Apartments at 1020 W. Lawrence Ave. Image courtesy: chuckmanchicagonostalgia.com

Lawrence House tells a story that is shared by many of Uptown's apartments. In the interwar period commonly referred to as the “Roaring Twenties,” Uptown saw the construction of many luxury apartments for the urban elite who were settling around the inner city.

A 1930 Chicago Tribune ad lists various luxury apartments, "exquisitely furnished" to "reflect the charm and refinement that appeals to the truly discriminating."

The Lawrence house apartments were advertised as being "just like a fine club," with facilities for genteel socializing and a life of comfort. Celebrities like Frank Sinatra and Henry Kissinger are known to have spent time in the building.

An early ad for the Lawrence House apartments promises that it is "just like a fine club." Images of the facilities and the young white men who are the architects all clearly seek to appeal to "respectable" elite consumers.

With the Great Depression, however, these apartments emptied out and fell into disrepair as Chicago struggled. At this time, no new "hotels" of this kind were built. Instead, apartments like Lawrence House were partitioned into smaller, cheaper apartments to house the thousands of poor people flocking to the city searching for jobs. Many of them became "SROs" or single-room occupancy apartments, where the tiny rooms had barely any ventilation, and were not maintained by landlords.

Some erstwhile luxury apartments like the Wilson Men's Hotel came to be known as "cage hotels" because the walls did not go all the way to the ceiling to facilitate ventilation, and were instead covered by wiring.

Source: www.chicagohomeless.org. Copyright: Mark Brown, Sun-Times, 2016.

These were filled by poor people of extraordinarily diverse circumstances—white Southerners, Native Americans, African Americans, Puerto Ricans, Japanese Americans who were moved from internment camps during World War II, and international refugees from various war-torn countries. In addition, laws that shut large state mental asylums in the US also led to mental health patients being moved into SRO's to receive apparently more humane "community care," in reality facing poverty and abandonment. This was what made Uptown a major site for multiracial alliances by poor people in the 1960s.

Performance artist Anndrena Belcher speaks about meeting people from all over the world at school in Uptown who were pushed off their land like her and her family. Source: America’s War on Poverty Part 1: In This Affluent Society. 1995. Documentary film. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Courtesy: Henry Hampton Collections, Washington University Library.

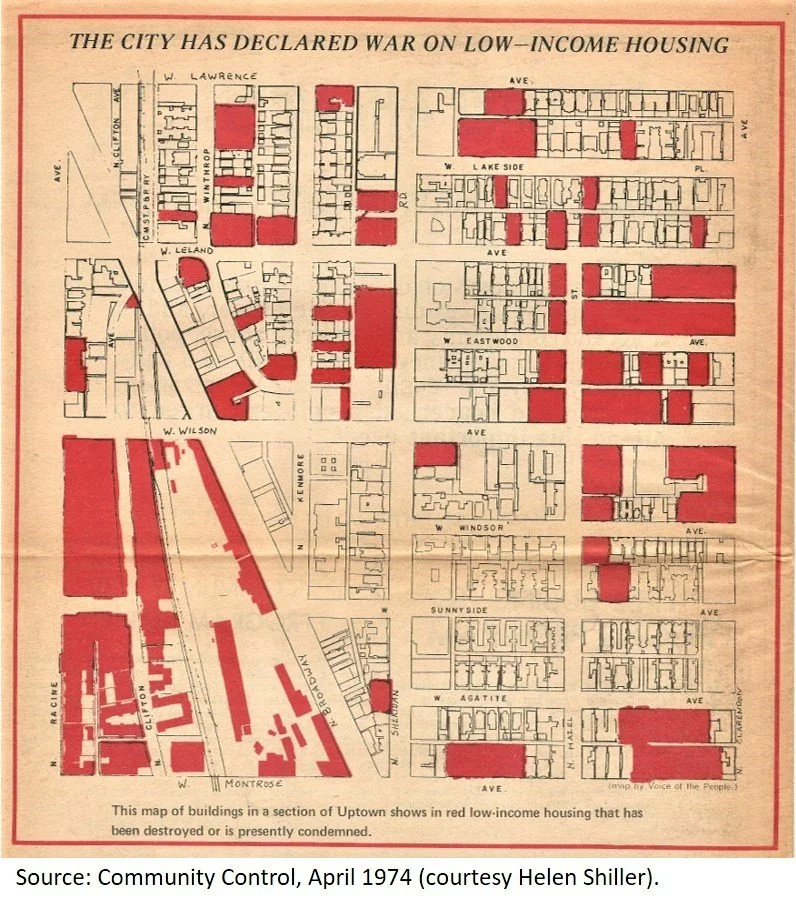

This map in the April 1974 issue of the Community Control newsletter shows the large stretches of low-income housing that has been razed or is in the process of being redeveloped. Courtesy: Helen Shiller.

The landlords who took over these repurposed buildings had no incentive to maintain or secure apartments for residents who were on welfare or earning the bare minimum. The city authorities ignored these issues. As buildings degenerated for lack of care and crime flourished, Uptown's slum-like conditions and its "slumlords" gained notoriety. When the economy recovered in the 1970s, developers, encouraged by the city's stance on urban renewal, began eyeing the prime lakefront property on Uptown. Slumlords were now eager to sell their land to developers, and sought ways to remove the poor residents of their buildings.

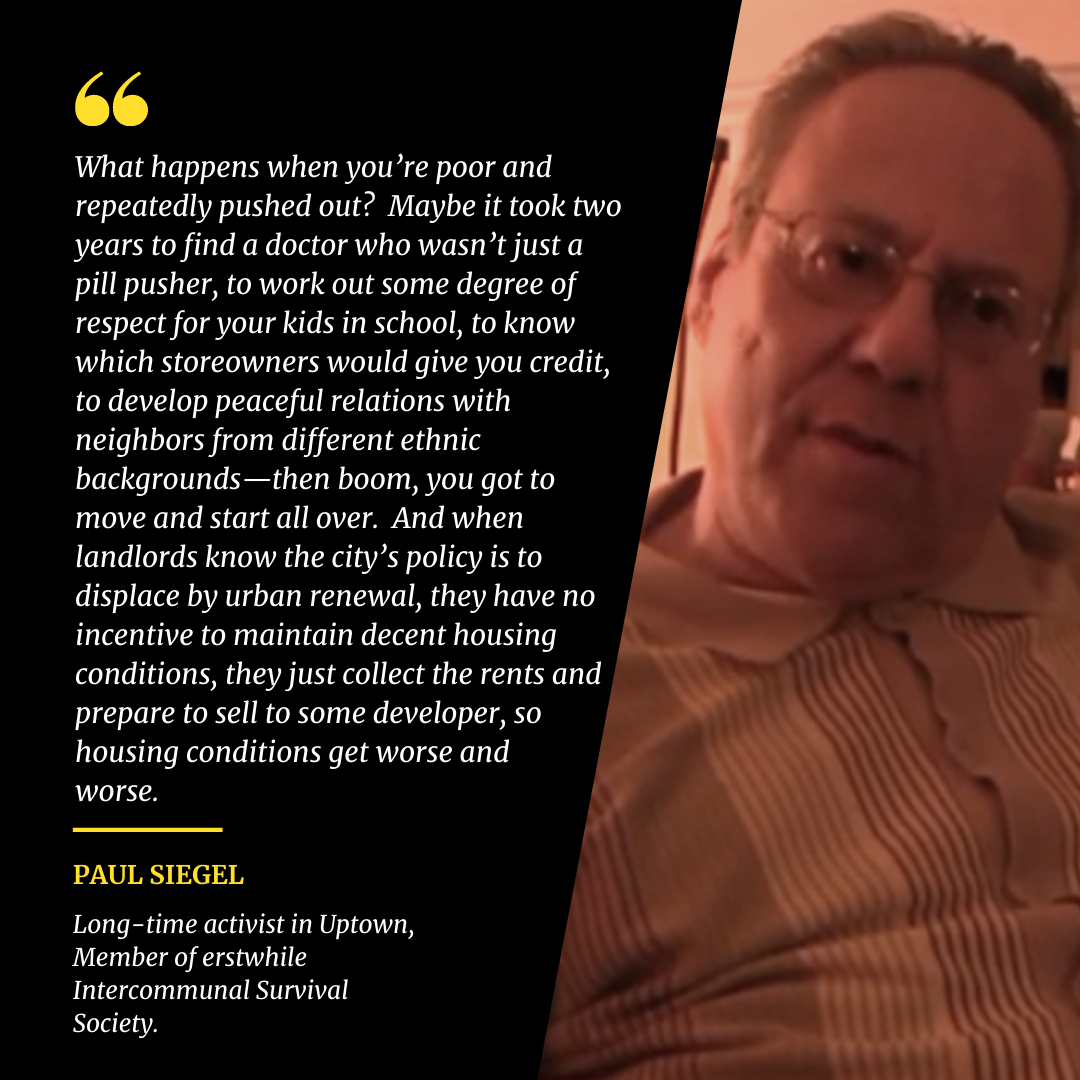

Paul Siegel, member of the erstwhile Intercommunal Survival Committee and longtime organizer in Uptown, reflects on what it means to be constantly displaced from one's home.

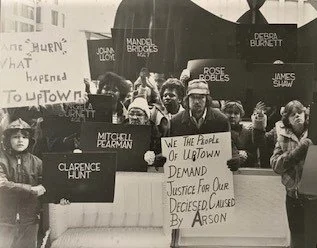

For the elite of Uptown, who found Uptown's slums to be disreputable, unsafe, and bad for investment, this was a welcome turn of events. But for the poor, this meant that they were being forcefully moved out of their own homes through illegal and violent practices like arson. 'Arson for profit' and deaths resulting from these actions became common.

This photograph captures a protest against arson staged in Chicago's downtown by Uptown residents. The boards held up name those who died in the fires and demand justice for them. Credit: Helen Shiller.

An issue cover and an excerpt shows Keep Strong's in-depth coverage and exposure of arson as a systemic malpractice. Source: Keep Strong newsletter, February 1980 [cover; courtesy Helen Shiller]; Keep Strong newsletter, March 1977, p.23 [excerpt].

Marc Kaplan, a longtime Uptown organizer, talks about the arson wave that the community successfully fought in the 1980s. Image credit: Phil Cantor, Teachers for Social Justice

The various community organizations in Uptown took up struggles against the city and slumlords. Following JOIN, the Intercommunal Survival Committee organized poor tenants in these apartments into Tenant Survival Unions, enabling them to collectively push for change by withholding rent. Against the city's plan for urban renewal, named "Chicago 21," the ISC mobilized people around a People's Plan to demand that city development policies did not only aim to attract elite residents and businesses, and instead focused on public services including affordable housing.

In this September 1976 interview with Uptown organizer Slim Coleman, he warns Uptowners of the Chicago 21 Plan, set to attract funding for large-scale urban renewal projects, and its ripple effects in all poor communities around Chicago's Loop area. He emphasizes that the plans for "their city" "don't include us."

We saw the early struggles around Hank Williams Village. Another watershed moment was the Avery lawsuit in 1970, where Uptown's low-income community sued the city for colluding with developers to drive out marginalized poor people, largely people of color, and fill neighborhoods with wealthier, largely white, populations. They were pushing against a particular developer, Bill Thompson, notorious Mayor Richard J. Daley's ex-son-in-law, who had strong connections in the government, and bought up several buildings in Uptown for redevelopment. Though Uptown did not win the lawsuit, Thompson's projects were stalled for years, and he was forced to negotiate with poor Uptowners.

Another important wave of housing struggles were around the buildings that were subsidized by the HUD (Housing and Urban Development) authority in the 1980s. This was a time when, nationwide, SROs and other kinds of affordable housing were disappearing, pushing poor people into homelessness and precipitating a crisis. Tenants in Uptown's HUD buildings collaborated with community organizations like ONE Northside and Voice of the People (both of which exist even today) to together push out their corrupt landlords, and to get nonprofits to acquire, upgrade, and maintain the building without evicting existing tenants. The leaders in most cases were single mothers on welfare, many Black.

A 1996 report by Loyola University foregrounds the women who led the HUD housing struggles in Uptown's various buildings.

The "4848" on Winthrop Avenue was a HUD building that became infamous as a "crime hub," and subject to excessive police surveillance that exacerbated tensions. Today, it is a fully tenant-owned cooperative, a far cry from the 1980s.

Affordable housing and "development without displacement" was the motto Helen Shiller campaigned on when she won the elections to be Alderwoman of the 46th Ward with the support of Chicago's first Black mayor, Harold Washington. She was a longtime Uptown organizer with the Intercommunal Survival Society. Her track record helped her get elected for 6 consecutive terms, and she was Alderwoman until 2011. Thanks to her consistent advocacy for the poor, she was highly unpopular among Uptown's wealthier residents and the political machine.

In a 2012 interview with Jose "Cha Cha" Jimenez, Helen Shiller reflects on her commitment to affordable housing during her tenure.

Courtesy: Grand Valley State University Digital Collections. Copyright: Jose Jimenez.

One of Shiller's biggest contributions was the Wilson Yards TIF project, where she pushed to have the Wilson Yards area in Uptown classified as a TIF area. However, TIFs have been highly controversial as a means of urban redevelopment, most commonly used to push out poor populations, and Shiller gained the ire of even some of her allies with this move.

Watch this short clip to know what TIFs are, why their use in neighborhoods like Uptown is controversial, and why TIFs are often opposed by poor communities in the city

Nevertheless, after 12 years of legal and political struggle, Wilson Yards was realized as a prime example of "mixed-model development." Unlike most TIF areas, in this case, apart from attracting large private businesses, TIF funds were used to build four residential buildings of affordable housing (615 apartments for low-income families), provide funding to four small local businesses, and to add facilities to two public schools and one public university.

This map of the Wilson Yards TIF area lists civic/institutional projects, affordable housing, and public schooling as among the main investments.

What happened to SROs and subsidized housing in the years between the 1980s and today? Many of them, sadly, were redeveloped despite this resistance. Lawrence house was converted into a luxury condo, as was Wilson Men's Hotel. They were restored to their "twenties glory," attracting wealthier tenants, and condemning former tenants to homelessness. The last of the SROs in Uptown such as the Lorelai and Darlington Hotels have also been slated for "renewal," greatly contributing to the housing crisis and the increasing population of the homeless in Uptown. The Tent City struggle since 2016 is a product of such displacement. Many of those who were pushed out of these SROs began living in tents under Uptown's viaducts. Their tents were forcefully removed with no alternatives provided by city authorities, an illegal move that was met with resistance from Tent City's residents, who have elected to remain under the viaduct in Uptown.

Tom Gordon, a major figure in the protests by the evictees of Tent City, talks about people's right to live where they need. Image credit: Social Justice News Nexus

With the support of members of JP-USA, a social justice-oriented religious organization, and the Uptown People's Law Center, which began as part of ISC efforts in the 1970s, Uptown's homeless continue to fight for their basic right to shelter.

Copyright ©2018 Dis/Placements Project