Survival Pending Revolution

Survival pending revolution

Site #6 description…

This site is where the Uptown People's Health Center (4824 N Broadway) was set up as a result of ex-miners organizing in Uptown. Listen to this audio clip of one of them, Buddy Blankenship, talking to renowned broadcaster Studs Terkel. Interview begins around 40 minutes & 13 seconds into the program: https://studsterkel.wfmt.com/programs/terkel-comments-and-presents-hard-times-oral-history-great-depression-chapter-7-0

Courtesy: The Studs Terkel Radio Archive ("Hard Times: an Oral History of the Great Depression"; Chapter 7)

Survival as a Radical Goal

Above: Huey P. Newton on the idea of survival pending revolution. He wrote that "these programs satisfy the deep needs of the community but they are not solutions to our problem." Below: A Keep Strong article notes that what makes the Black Panther Party so dangerous to people in power is their survival programs.

Sources: To Die for The People: The Writings of Huey P. Newton, 1972 (above) and Keep Strong, November 1977 (below, courtesy Helen Shiller).

The "survival programs" of the Intercommunal Survival Committee (ISC), an organization led by a group of radical students in the 1970s, followed the Black Panther Party's model of attending to survival as integral to politically organizing the working class. The survival programs were so successful that they eventually grew into centers and organizations that exist even today, such as the Uptown People's Law Center.

Affordable food and healthcare for the poor are often implicitly seen as a matter of charity and basic subsistence, and this view informs discriminatory attitudes in the public health and welfare system. However, several extraordinary movements in Uptown have fundamentally challenged this idea, asserting that food and health are basic rights that poor people are entitled to as citizens, and that survival, as much as ideology, needs to be the building block of radical social change.

The Young Patriots begin this report on their new health center by declaring, "We are fed up with being treated like cattle!" They invite poor Uptowners to use their free services where medical workers won't "get rich off of" them. Source: The Firing Line, n.d. (around 1969). Courtesy: Peggy Terry Archives, Wisconsin Historical Society

One of the earliest examples of such an initiative is the Community Health Center set up in 1969 by the Young Patriots Organization, which later became part of the Original Rainbow Coalition. While the government had set up a community clinic in Uptown, it was understaffed and open only until 5pm on work days, hours that did not work for the working class who only got off work at 5pm. The YPO took up this cause and protested in front of this government community clinic. When their protest did not result in any change, they began an alternative clinic with the help of volunteer medical staff. The YPO clinic, however, faced several legal challenges from the Daley "machine":

This report on The Firing Line newsletter details one of the court battles between the Chicago Board of Health and the YPO health center, where the city tried to close down the people's clinic through bureaucratic demands like licensing, which was not required of for-profit clinics. YPO won the case, and the licensing rule was struck down as unconstitutional.

Although the health center and YPO eventually succumbed to government repression and violence, it created a political base to organize around the issues of adequate healthcare and food security. The ISC's survival programs built on this base, and directly addressed "poor people's diseases." These illnesses included hereditary disorders such as Sickle Cell Anemia, that disproportionately impact African Americans, one of the poorest and most historically disenfranchised communities in the U.S, as well as life-threatening conditions that working class people developed working in poorly paid and unsafe jobs like mining and factory work.

This 1977 article in the Keep Strong newsletter calls out the medical establishment's ineptitude in attending to "poor people's diseases" like Sickle Cell anemia and black lung disease. They argue that diseases like polio and cancer, that also affect the rich, see billions of dollars of investment.

Poverty is Slow Death: Lead Poisoning

Lead poisoning was one such health concern. We saw how slumlord malpractices led to dangerously dilapidated housing conditions for the poor communities of Uptown. A specific danger, particularly for young children, was the high levels of lead in the paint. Though landlords were legally obliged to ensure that the lead-intensive paint once used in old buildings was replaced with safe paint, they often simply painted over it. Peeling paint led to the lead being exposed. Small children often swallowed peeling flakes, especially if they had a mineral deficiency-related condition called "pica." As was well known, even then, lead poisoning can lead to disorders in brain development and even death. In its early days, lead poisoning as an issue was taken up by the "welfare mother" activists of JOIN.

This handmade poster by JOIN from the 1960s informs Uptowners about a free lead-testing session at the Montrose Urban Progress Center. The poster lists the symptoms of lead poisoning, and tells residents they can sue their landlords for maintenance and compensation.

Uptown has seen movements at various points to address this issue. In the 1970s, at the height of anti-war protests, lead poisoning protests featured slogans like "Lead in the Ghetto, Napalm in Vietnam," connecting the US government's pro-war foreign policy with its lack of care for human life in domestic politics.

A Rising Up Angry issue on lead poisoning declares above a photograph of protestors, "Good Health is a Human Right." Source: Rising Up Angry, vol. 4 ,no.1. Courtesy: University of Illinois Library Special Collections

In the 1990s, parents and educators joined together to address the issue, successfully sued negligent landlords, and fought against a bureaucracy that protected landlords rather than tenants.

Karen Zaccor, educator and activist in Uptown who founded the UPLIFT Community High School in Uptown, recalls the campaign against lead poisoning in the 1990s which contributed to the rehauling of outdated and cumbersome city-wide regulations

Ex-Coal Miners Demand Healthcare

Poor people faced—and continue to face—various kinds of slow death because of structural conditions and poor quality of life. That said, today, there are far more laws protecting poor people's rights as workers, healthcare-seekers, and citizens. This is because of hard-won legal and political reforms owing to "poor people's power" movements. One such victory, the national movement for better recognition of "black lung disease" among ex-miners, had its roots in Uptown.

This mural was drawn by 11 year-old Pamsey Gay, granddaughter of an ex-miner whose mother, Judy Branham, was a major organizer for black lung rights. It visualizes Pamsey's nightmare, where she saw two dead miners coming out of the mines in a coal car. At the time, it was a somber reflection of the deaths of many ex-miners from black lung in Chicago. Most of them would have survived with affordable healthcare and employment assistance. Pamsey Gay's nightmare was painted on the wall of the Heart of Uptown's Fred Hampton Memorial Hall at 1222 W. Wilson Avenue. Sadly, the building has since been repurposed and the mural lost. Courtesy: Paul Siegel.

As part of its outreach work among the Appalachian migrant community in Uptown in the 1970s, the Intercommunal Survial Committee (ISC) found that hundreds of them suffered from black lung disease, a popular term for a range of lung disorders caused by coal dust settling in the lungs. Those like Branson “Buddy” Blankenship had worked for decades in the mines of Appalachia, and had migrated to the city during the Depression.

Blankenship interviewed by Terkel. Caption: Listen to this audio clip of Buddy Blankenship talking to renowned broadcaster Studs Terkel. Blankenship talks about the experience of working in depleting coalmines for a pittance. Courtesy: The Studs Terkel Radio Archive ("Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression"; Chapter 7)

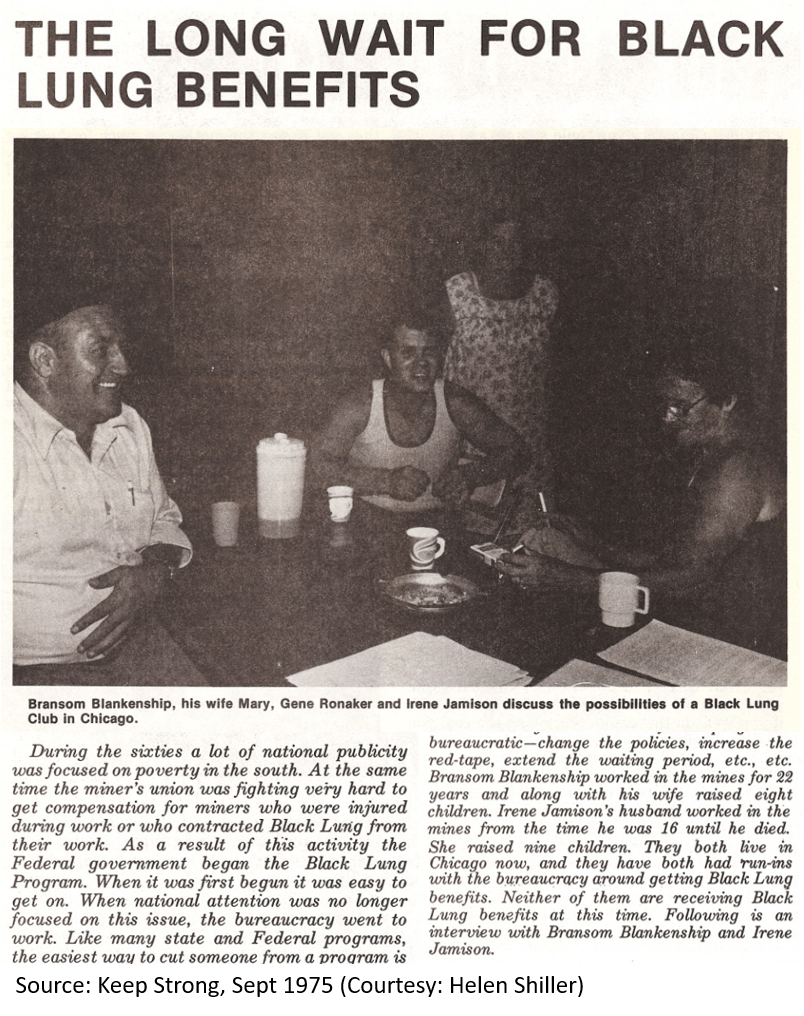

In cities, doctors rarely understood black lung disease, and ex-miners were disconnected from worker support networks back in Appalachia. Laws in place to ensure free healthcare for black-lung sufferers were ineffective: filing for claims and benefits was mired in daunting bureaucratic procedures. Many ex-miners died, unable to find other employment because of their illness, while waiting for benefits that never came. ISC brought together people from the Appalachian community to think about a "black lung club" to organize for benefits.In cities, doctors rarely understood black lung disease, and ex-miners were disconnected from worker support networks back in Appalachia. Laws in place to ensure free healthcare for black-lung sufferers were ineffective: filing for claims and benefits was mired in daunting bureaucratic procedures. Many ex-miners died, unable to find other employment because of their illness, while waiting for benefits that never came. ISC brought together people from the Appalachian community to think about a "black lung club" to organize for benefits.

The September 1975 issue of Keep Strong magazine featured an interview with Bransom Blankenship and Irene Jamison, the former an ex-miner and the latter an ex-miner's widow.

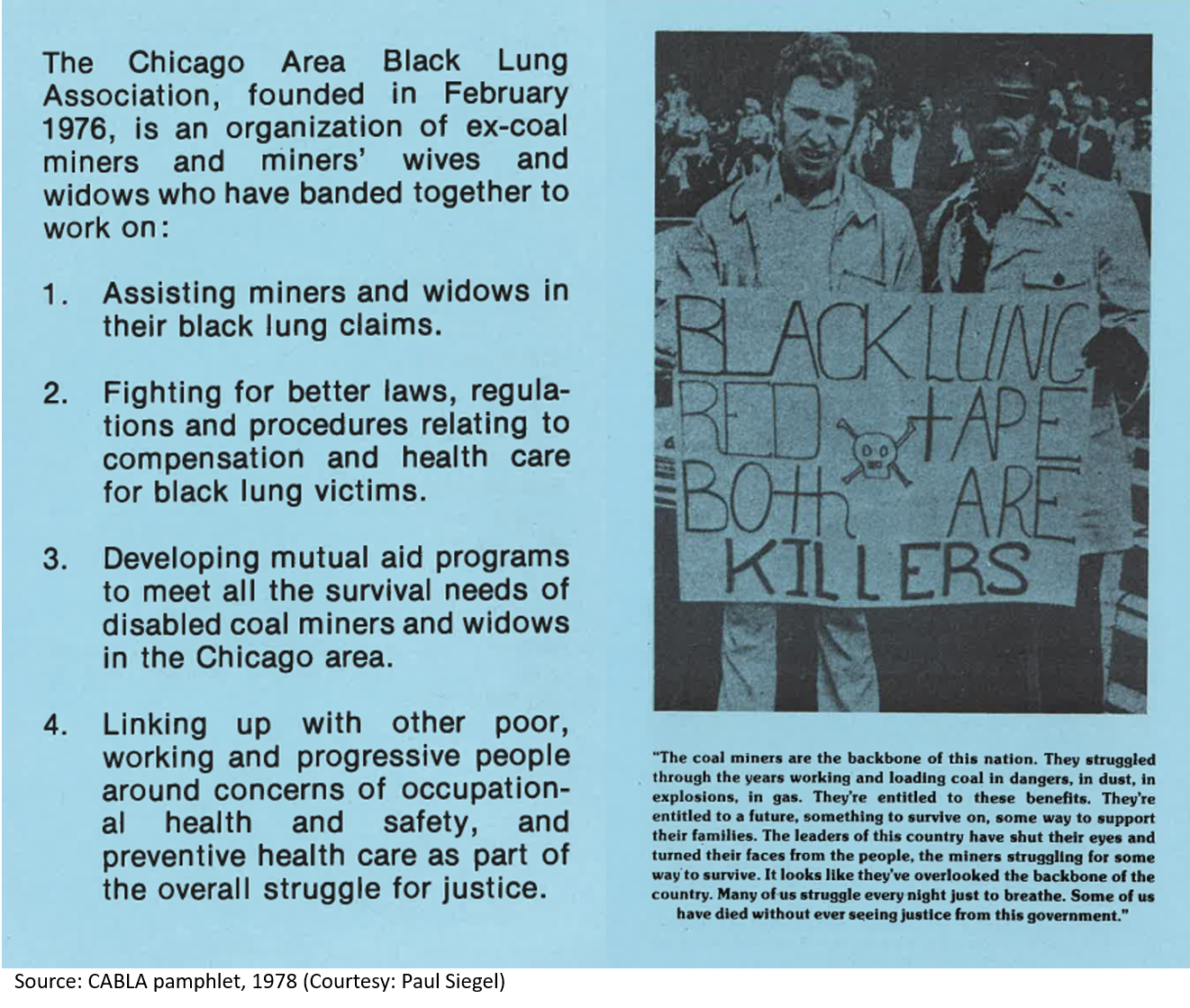

What resulted was bigger than anyone ever thought possible: the Chicago Area Black Lung Association, which brought together thousands of ex-miners and their families across Chicago, staging high-profile protests against the Chicago Board of Health's refusal to recognize black lung as an urgent health problem.

A CABLA pamphlet outlining its agenda: fighting for black lung claims, mutual aid, and coalitional poor people's politics. Courtesy: Paul Siegel.

In 1976, after several protests against the Chicago Board of Health's unwillingness to listen to miner's assertions that black lung is a widespread issue, CABLA set up a large gathering in Uptown including Federal government representatives, members of the press, and ex-miners. Several ex-miners and families gave powerful and harrowing testimonies to their suffering under a bureaucracy that literally pushed them to their deaths. Source: Keep Strong, November 1976.

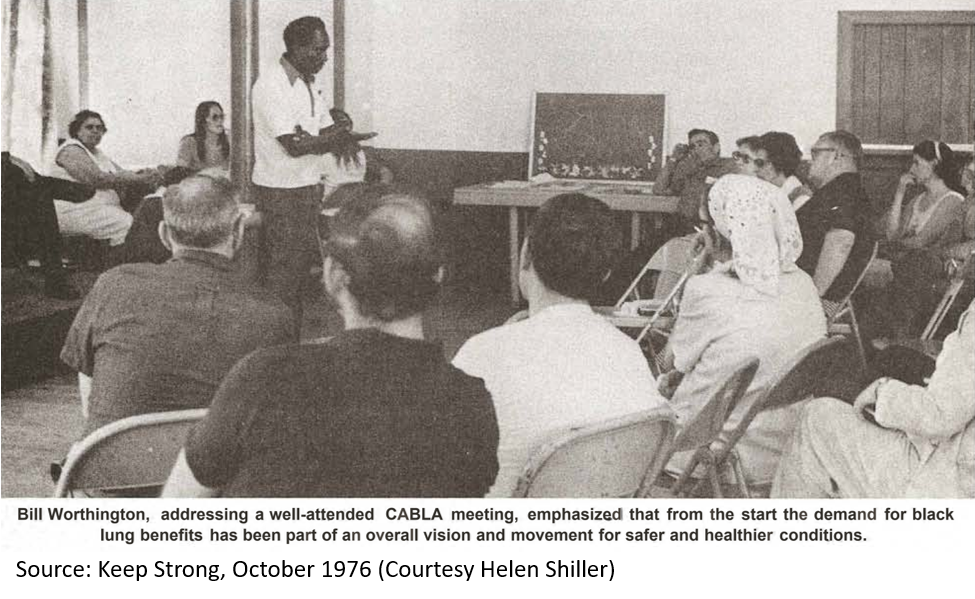

Mobilizing around black lung meant that white Southerners had to overcome racist attitudes to stand with Black ex-miners. CABLA, under the guidance of Bill Worthington who led a broader regional movement of ex-miners, became part of a fully national movement.

Bill Worthington was a workers' leader who organized in mining areas for black lung benefits. In alliance with him, CABLA became part of a national movement. Here, he is shown speaking to CABLA members in Chicago. Source: Keep Strong, October 1976. Courtesy: Helen Shiller.

The grassroots movement was a resounding success, thanks to the untiring efforts of organizers such as Bill Worthington, Branson Blankenship, Lawrence Zornes, Irene Jamison, Marc Zalkin, Jim Chapman, Sarah Dotson, Dave and Jimmie Baisden, Judy Branham, and Paul Siegel. The positive outcomes included successfully fighting for claims for hundreds of ex-miners, making simpler and more effective Chicago's process for accessing black lung benefits, and most importantly, the Uptown People's Health Center, set up in 1978, which specialized in detecting and treating black lung. Eventually, this led to better facilities for black lung treatment in Illinois and the country at large.

Movements for health and food security continue to form the backbone of poor people's power in the US even today. Uptown's various tactics for ensuring "survival pending revolution" continue to resonate and inspire present-day organizers, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic and its disproportionate effects on poor people of color.

Present-Day Survival Struggles

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 was the final straw for a public health system subject to decades of commercialization and cost-cutting. Black and Latinx working-class people died in disproportionate numbers. Uptown activists, many who were part of the movements we saw so far, became part of a Chicago-wide coalition demanding for poor people's healthcare rights: People's COVID-19 Response. National-level meetings drew attention to existing socialist models of healthcare in places like Cuba, which had fared far better during the pandemic. More short-term measures like COVID-19 testing camps were also conducted in neighborhoods like Uptown.

A flyer for a COVID-19 testing drive organized in 2020 reminds residents that "COVID + Flu + Racism + Eviction = A Community Health Crisis."

We thank longtime Uptown activists Paul Siegel, who worked extensively with CABLA in the 1970s and 1980s, and Karen Zaccor, who organized around lead poisoning in the 1990s, for their notes and source material.

Copyright ©2018 Dis/Placements Project